Posts Tagged ‘A-Pis-Chas-Koos’

Harlan: A Tragic History – Chapter 2 of 6

Photo (Frog Lake Memorial): One man who died was the John Delany, the Grandfather of my Aunt Hazel (wife of my mom’s brother Melvin Wheeler), all part of the interesting history of our family. Note, many of these historic signs still denote the event as a Massacre in the midst of the Northwest Rebellion. Little mention is made at these historic sites of the attempt by an “Indian Agent” follow the “letter” of the laws passed in Ottawa, to starve the local bands into full submission to his wishes.

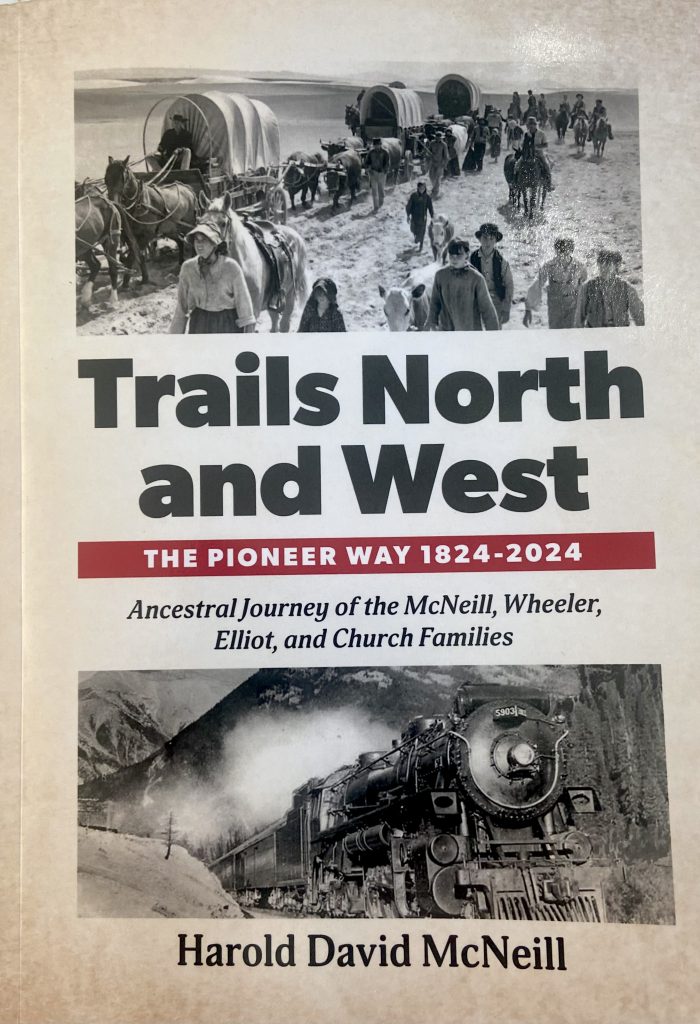

The full story, including this Chapter, is now in book form;

This Book is available from

Kindle Direct Publishing

Book 2 -Trails North an and West: The Pioneer Way 1824-2024 is now available from Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) You can search by book title or author name. A preview of the first seventeen pages is provided (link on bottom left on the KDP order page). The preview also includes the Table of Contents.

Note: When ordering four or fewer books, they will be printed and shipped within Canada. An order of 5 or more books may be printed and shipped from the United States. Postage is included in the purchase price when ordering from either country.

If you are thinking of sending books as gifts to others, you may consider having those books mailed directly to the recipient(s), by Amazon, at time of ordering. In this way, you would avoid Canada Post fees which currently run about $20.00 (plus tax) for one or two books, if enclosed in a single mailer.

For more background information on the story, go to the lead story on this blog.

Cheers,

Harold

Link to Next Post: Snakes

Link to Last Post: Old School House (First of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

Link here to photo’s of Frog Lake adventure: LINK HERE

Also, a note by Phylis Wicker Glicker

Hazel Martineau [Wheeler] daughter of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau b. Oct. 18, 1875, St. Boniface, Manitoba, Canada, and Margaret Delaney b. Nov. 30, 1885, Frog Lake, Alberta, Canada. Adrien is the son of Herman Martineau b. Brittany France mar. (1) Annie Macbeth (2) Angeline LaBelle. Herman Martineau is the son of Ovit Martineau b. Brittany, France. I have just begun researching the Delaneys and Martineau”s so I don’t have much. But I would love to hear from you and share what I have. I was married once to Frank Martineau, grandson of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau and would love to learn about Margaret Delaney’s family for mine and my children’s sake.

Email: pwicker@telus.net

(4217)