Fire Walkers: Chapter 1 – A Nuclear Challenge

Photo (1961): USAF Crash Rescue Crew From Cold Lake taken while in training at CFB Camp Borden

(Photo: Courtesy of Guy Venne)

Top Row: U/K, Ken Cuthbert, Les Eshelman, Al Edstrom, Ed Vallee, George Grimstead, Morris Hill,

Wally Armstrong, Fred Bamber, Roy MacDonald, U/K, Art Axani

Front Row: U/K, Instructor, Instructor, Harold McNeill, Instructor, Guy Venne, Instructor, U/K,

Denis Armstrong, Derek Bamber, U/K

(All names subject to clarification — Click photo to open, then click again for full-size download or printing. Names in bold, all Cold Lake High School buddies)

October 14, 2017 (4200)

Fire Walkers: A Nuclear Challenge

2011 will mark the 50th Anniversary of a unique experience in my life and that of several friends and neighbours from the Cold Lake area of Alberta. Forty-five men, ranging in age from twenty to thirty-eight, were selected to work as Civilian Crash Rescue Firefighters for the US Air Force at the Strategic Air Command base being built at the RCAF Station Cold Lake. For a full list of names of those selection Link here to Chapter 6,

Two other SAC bases built in Canada were also selecting civilians to perform the same duty – 45 for Namao (just outside Edmonton) and another 60 for Churchill in Manitoba. All were to be trained over the summer and fall of 1961 at the Crash Rescue Fire Fighter School in Camp Borden, Ontario, a school that had an established reputation as being the best in the business.

While a few of the men destined for Cold Lake had small town, volunteer firefighter experience, most, including myself, were taken in as raw recruits. Over a period of five months spread over two training groups, the men moved from the training stage to manning a full-service Fire Department. This included a process to select a Fire Chief and Crew Chiefs from within the ranks of those trained at Borden.

The expedited process resulted from the reluctance of the RCAF, in the politically charged climate of the deep Cold War, to have RCAF personnel fully integrated into what was essentially an independent USAF operation on Canadian soil.

For their part, the USAF was not able to field a sufficient number of firefighters to perform this duty due to a rapidly expanding Cold War Strike Force that stretched around the world. This included manning over 450 SAC bases within the continental United States, Alaska, and Hawaii.

Force that stretched around the world. This included manning over 450 SAC bases within the continental United States, Alaska, and Hawaii.

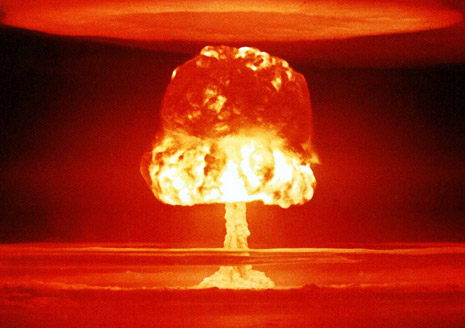

The threat of a nuclear attack and potential annihilation of mankind was one of the most feared events throughout the 1950s and 60s. The proliferation of nuclear weapons following the Second World Wars and the resultant partition of Europe lead to almost continuous conflict from 1914 through 1975 (the end of the Viet Nam War).

An all out Nuclear War between the Western Democracies and Russia would most certainly have ended life on earth as we know it. By way of comparison, the current day “war on terror” is a rather trivial event.

It was a time in our history when the Cold War mentality paralyzed much of the world and a time when Canada hosted a nuclear arsenal that was globally fifth in size behind only the United States, Russia, England, and France. The nuclear weapons in Canada, the subject of secret agreements, were stored across the country as well as carried aboard giant B52 bombers that circled high in the skies above the Canadian Arctic twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. The giant USAF Base at Goose Bay hosted between 12,000 and 15,000 USAF personnel in what was one of the largest USAF bases outside the United States.

The proliferation of nuclear weapons and a massive build-up of SAC bombers, as well as support aircraft and personnel, was a hot-button issue in Canada for almost 20 years. This story tracks the experience of that small group of men from Cold Lake who became a small part of the much larger story of Canada’s involvement in fighting the ‘Cold War’, a war that began in the 1950s and continued through to the end of the Viet Nam War. Join the Fire Walkers from Cold Lake as these young men embark upon on an exciting new challenge.

Fire Walkers: Flying into a Firestorm

A large plume of thick black smoke rising some distance beyond the horizon sent a shiver up my spine. It was obviously oil based and was coming from the direction of the RCAF Station at Cold Lake. My first thought – perhaps a CF-104 jet fighter had crashed, or it could have been one of the giant US Air Force K-97 refueling tankers stationed there. The volume of smoke surging several thousand feet into the sky suggested a fire of much larger proportions than the crash of either a fighter jet or even a fully loaded tanker. A bomb?

In the early afternoon, the sun was high in the sky and the weather calm as I climbed through 2000 feet heading toward the plume. It was my third day off from duties at the SAC base and had borrowed a small seaplane to make a trip to LacLaBiche, about 125 miles northwest of Cold Lake, to visit some friends I had lived with while hauling fish from various small lakes in that area.

In the early afternoon, the sun was high in the sky and the weather calm as I climbed through 2000 feet heading toward the plume. It was my third day off from duties at the SAC base and had borrowed a small seaplane to make a trip to LacLaBiche, about 125 miles northwest of Cold Lake, to visit some friends I had lived with while hauling fish from various small lakes in that area.

As I continued, I fervently hoped no one had been killed or injured and that my comrades in the Fire Department were all OK. In twenty minutes I would radio the Cold Lake Tower to provide notice of my position and estimated time through the northern edge of the control zone.

Although I was not landing at the base, contact with the Control Tower was mandatory and, as well, most civilian pilots used the Base Flight Services to file cross-country flight plans. It was also mandatory to obtain permission to enter any portion of the Restricted Zone known as the Primrose Air Weapons Testing Range; today, however, I would skirt the southwest corner of the range.

While RCAF tower personnel were extremely helpful to civilian flights, which included the restricted use of the runways, it had to be remembered it was still a military base that followed strict security protocols. As far as we were concerned, with Russia, our northern neighbour, and the United States on the south locked in a deadly game of nuclear brinkmanship such as that which occurred during the Cuban Missle Crisis, World War Three, was just button push around the corner.

Background: The Cold War of the 50s and 60s

As the Cold War continued to build through the 1950s, fear of communism reached epidemic proportions in the United States as men like Senator Joseph McCarthy stoked the fires of fear in his desperate search for communists, communist sympathizers and even persons who might have at one time known a communist. The US government, military, and media continued the spin by speculating on the possibility of Russia launching a sneak nuclear attack.

US State and Federal Governments, as well as average citizens, were building bomb shelters by the thousands and school children were required to participate in regular training designed to ‘shield’ them from the effects of an atomic blast.

In Canada the general public, while well aware of the dangers posed by the nuclear build-up, took a much phlegmatic view. The Federal Government, on the other hand, first under the leadership Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, then Liberal Prime Minister Lester Pearson began building shelters across the  country – shelters to shield Senior Government and Military Leaders in the event of a Russian attack. These bunkers became derisively nicknamed “Diefenbunkers” by the public and press.

country – shelters to shield Senior Government and Military Leaders in the event of a Russian attack. These bunkers became derisively nicknamed “Diefenbunkers” by the public and press.

In a little know side story of political intrigue, a Junior Cabinet Minister in the Pearson government, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, resigned his cabinet post in protest to the secret approval to move more nuclear weapons into Canada.

After Trudeau assumed power as Prime Minister in 1968, all nuclear weapons were removed from Canada. This quickly led to our own Canada-US small “c” cold war. The negative position Canada took toward the Viet Nam war also added to the challenges between the countries in much the same manner as did our reluctance to join the US/British invasion of Iraq.

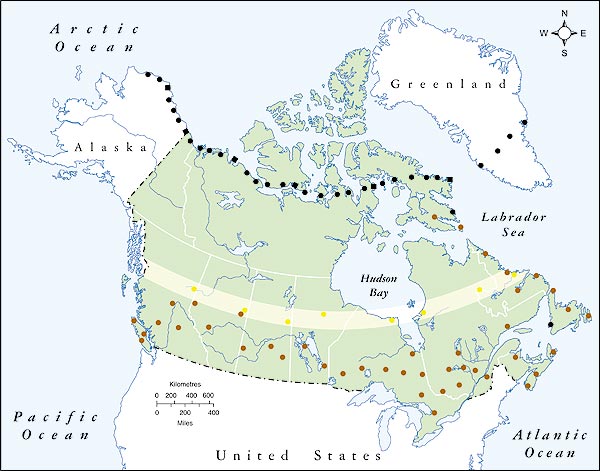

During the Diefenbaker and Pearson years, the US Government sought and received permission to build 63 Distant Early Warning Radar (DEW) Stations across the Canadian High Arctic as well as another 40 across mid-Canada, the Pinetree Line.

These radar stations, stretching from the western reaches of Alaska to eastern shores of Greenland, were designed to provide a continuous screen that would detect any Russian aircraft encroaching upon northern Canadian airspace. In addition to the radar stations, the large contingent of USAF personnel at Goose Bay manned a nuclear strike force capable of reaching Eastern Europe. As well, Canada maintained a fleet of Argus surveillance aircraft that crisscrossed the Atlantic and the Norwegian Sea tracking Russian nuclear-equipped submarines.

During this same period, the RCAF received delivery of new fighter jets, the CF-101 Voodoo and CF-104 Starfighter, capable of carrying nuclear-armed bombs and missiles into battle. At the RCAF Stations in Cold Lake, Namao (outside Edmonton) and Churchill (Manitoba), the USAF was building new SAC bases to host the dozens of KC-97 Stratotankers needed to refuel their bomber force.

The sole purpose behind these massive defense systems was preparation for a sneak attack by Russians. USAF nuclear-armed bombers stationed high in the skies above Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland could, on a moments notice, launch a counterattack designed to decimate Russian cities and military facilities. The ability to launch such a deadly strike became widely known as “Mutual Assured Destruction” (MAD). The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, under the leadership of President Kennedy, took the world to the brink of that nuclear armageddon.

Photo: Two excellent books on US Nuclear Weapons in Canada were researched and written by John Clearwater. The books trace the political and military history as well as providing a complete list of US Military Installations in Canada. It includes the only reference I could find to the SAC Base at Cold Lake.

While these world challenging events were part of the thinking of the day, my immediate concerns as a young man just out of his teens were much more pragmatic – getting and holding a good job, building up my flying time, going to a party on the next weekend off and wondering whether that lovely young French Canadian girl I was dating was still mad at me about the drive-in ‘incident’ with another girl. Such were the priorities of a twenty-year-old Canadian farm boy in the 1960s.

The first batch of twenty-four recruits from Cold Lake, the group to which I was assigned, was to leave for training in Camp Borden in late July with the second group to follow in October. USAF personnel from Nelles AFB and other US locations were assigned set up the SAC Fire Hall at Cold Lake and provide interim fire protection until our group finished training in October. The concept of hiring, training and forming fully operational fire department from scratch over a five-month period was an unprecedented and, as it turned out, a very successful operation.

It was an exciting time for everyone and although many of us had worked for the RCAF in various capacities – generally as day labourers during the school holidays – it was an entirely new level of challenge and opportunity to be fully integrated into the Air Force, especially the US Air Force Strategic Air Command, in a frontline capacity. Being able to do so while maintaining our civilian status was also considered a prerequisite as the younger single members of our troop had had our share of run-ins with the local RCAF chaps – mostly in matters dealing with their dating ‘our’ girls. The audacity of those air force guys knew no bounds.

A Personal Challenge

Before we were due to leave for Borden I encountered a personal challenge with my Driver’s Licence, a challenge that very nearly cost me the job. A firm requirement for being hired was holding a valid and subsisting Alberta Driver’s Licence. Although I had never been charged with any driving offence, my driving history from fifteen (when I first qualified for a licence) to twenty, on being hired, was less than stellar. On several occasions, I received verbal warnings from the town cop, Dick Skinty. The same happened in other towns and I had occasionally escaped being charged by the ‘skin of my teeth’.

As fate would have it, my dalliances behind the wheel of my 1954 Ford V8, finally caught up with me at a most inopportune time. In early June, not long after I had been selected to attend the Fire School, Constable Skinty observed me dropping a strip of rubber and driving in a ‘reckless’ manner along the main street in Cold Lake. He caught up to me a little later and issued a traffic summons requiring that I attend Provincial Court to have a judge review the matter.

At the hearing, the judge assessed a two-month suspension – I was devastated. It seemed certain it would cost me the job so after leaving court I approached Constable Skinty, with whom I was generally on good terms, and asked if something might be done to reduce the suspension to one month. To his credit and to my everlasting relief, he spoke to the Judge after court and I had my licence back within the month along with a stern warning that I simply had to stop driving like an idiot. Without any hesitation, I promised. Did I keep that promise? Well, yes, for the most part.

In late July 1961, our small cadre of firefighter want-a-bees was off to Borden.

Harold McNeill

February 2011

View from over the North Pole shows the proximity of Canada and Russia. USAF bombers, on a constant sortie over the Canadian Arctic, were within striking distance of Russia and Eastern Europe.

Location of the 63 Distant Early Warning Sites in the Northern Arctic and a further 39 sites, called the Pinetree (Mid-Canada) Line, were built in the late 1950s and early 60s. They stretched across Canada from the Alaska border and Vancouver Island in the West to St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador in the east. One site, still present, at Alsask, SK, is near the farm in which my Grandparents and mother (Laura) lived until 1924.

The radar installations were only a small part of the US presence in Canada during the 50s and 60s.

c1961 A KC-97 Tanker refuels one of the USAF SAC bombers high over the Canadian Arctic. This scene would have been repeated many times a day over nearly a decade. The bombers, loaded with nuclear weapons, were prepared to strike deep within Russia at the first sign of an attack against the United States.

(4772)

Tags: DEW, DND Firefighters, Cuban Crisis, B-52 Bombers, KC 97 Tankers, Cold War, USAF SAC, Nuclear War, Alberta, Crash Rescue Firefighters, Camp Borden, Ontario, Distant Early Warning Line, Cold Lake, Harold McNeill, Strategic Air Command

Trackback from your site.

Comments (1)