Changing the way police do business (Part II)

As in society, diversity within the police is all about being Canadian. The opportunities provided by working together in a common purpose, while recognizing and encouraging individuality, far exceeds any gains that might be made by forcing everyone to follow the same path.

Part I, Police solidarity and the push for amalgamation.

Part III, The past as a guide to the future

Part IV The integration of police services

Link to CBC Podcast: Policing in the CRD

Contact: Harold@mcneillifestories.com

(When reading this series it is recommended you start with Part I as each part builds towards the next.)

December 23, 2021: A recent report titled THE MENTAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING OF SWORN OFFICERS AND CIVILIANS IN THE VICTORIA, BRITISH COLUMBIA POLICE DEPARTMENT, is linked in this CTV News Report.

The full report bears directly on the substance of that which is discussed in the following article and it matters not which you read first. The substance of the two articles is linked.

The main difference between the two is how and when the challenges will be addressed. An existing danger in letting this tragic state of affairs continue is that at some point the dam will burst and if the points in this most recent report are accepted, that point is near.

PART II Comparing Differing Police Cultures

Originally, I intended to move directly to the process of implementing change within and between police departments but decided it was first necessary to compare and contrast the differing organizational philosophies that underpin each.

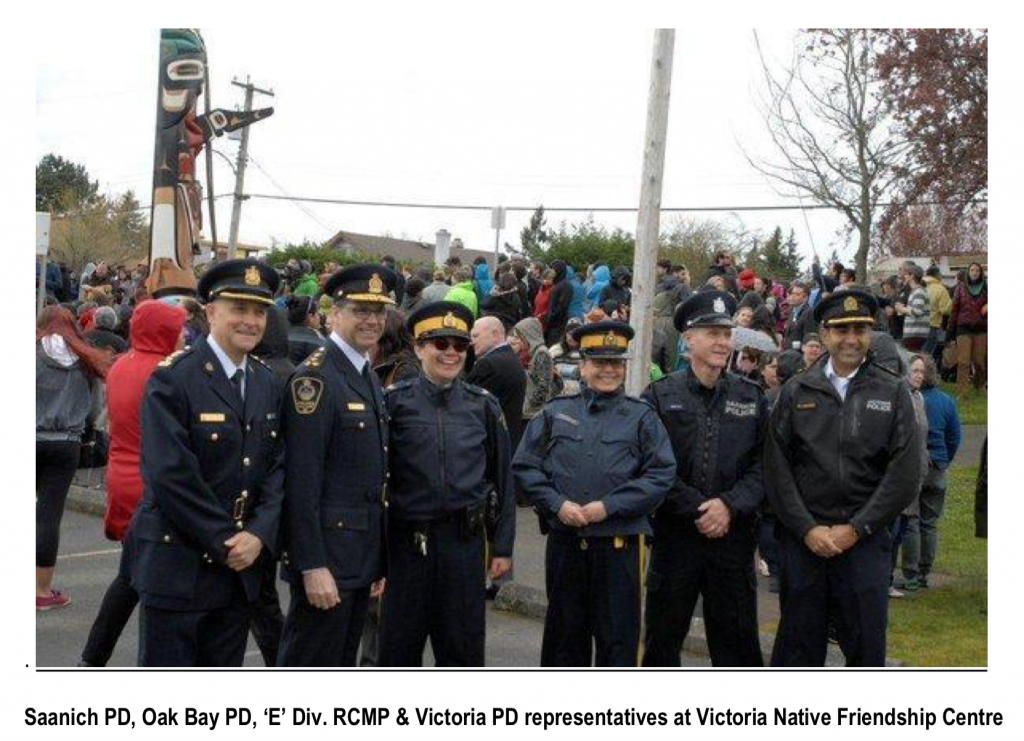

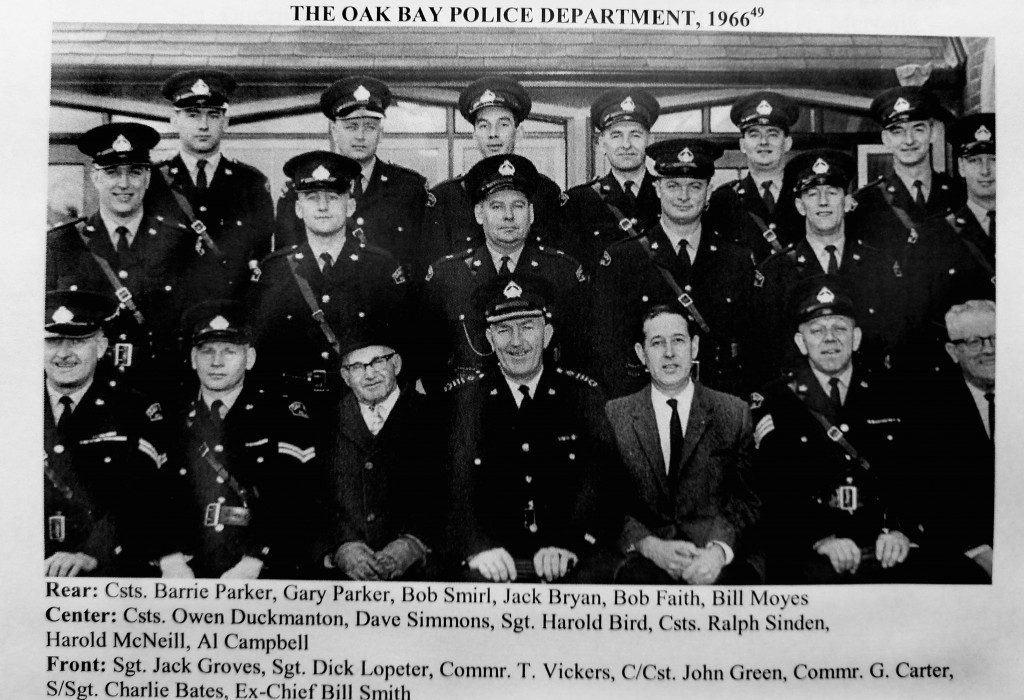

In Part I, it was posited that over their history, Oak Bay, Saanich, and Central Saanich have come to share a similar policing style. Victoria and Esquimalt, even before the merger in 2003, developed a very different style. The RCMP in the West Shore, North Saanich, and Sidney, being part of a national organization, have followed a path quite distinct from their municipal counterparts.

This part of the series will delve into the historical specifics of those differences as well as the positive and negative effects this has on each agency in the present day.

The history and process of implementing change will now be set over to Part III.

3. Introduction:

Within the CRD, a large part of the difference between departments is revealed in the historical events that shaped each. From the early 1960s to the present day leadership made all the difference. If leaders  nurtured the development of other leaders, they progressed, if they tended towards a command and control style, progress was slowed.

nurtured the development of other leaders, they progressed, if they tended towards a command and control style, progress was slowed.

While there are a time and place for Command and control leaders (times of crisis, etc.) they do tend to favour subordinates who follow rather than lead. Innovative, forward-thinking leaders, on the other hand, tend to encourage subordinates to take on leadership roles, the type of person willing to explore new ways of doing things. Until the 1960s, most police departments followed the Military/RCMP model of command and control, but over the decades since, many have moved towards a more progressive style.

It is also clear, the larger a police force becomes, the further leadership is removed from contact with the rank and file. In a heavily weighted, top-down system, leadership can lose sight of what is happening within the lower ranks. This is clearly a large part of the challenge faced by the RCMP in the current day and one reason behind that recent billion-dollar settlement with rank and file members.

To gain a better understanding of how we reached this point, and why some of the challenges seem intractable, take a few minutes to read Footnote (1), A Short History of Policing in the Capital Region. While reading, give some thought to the challenge of merging police forces that have evolved different leadership styles? Then, take a moment to think about private sector mergers and takeovers.

Friendly mergers of companies with similar styles and purpose are difficult but possible, however, if it’s hostile, the challenges can increase exponentially. In both cases, senior people in one company or the other is often forced out or demoted. The lucky few may have a golden parachute or enough power to secure an expensive buyout. In the worse case, it can end up in a protracted court battle. As for the workforce, some do OK, others can lose everything.

That’s not going to happen with a police amalgamation. Everyone, except the RCMP, has several layers of protection as well as a labour union to protect contractual rights. All contracts need to be rewritten, and in the process, no one is going to step back an inch without at least making an equal gain. Contract wording was developed over decades of negotiation, work to rule, and strike, so the highest common denominator becomes the default position.

Across the broad spectrum of management and union, it will be an expensive proposition and it could take years to hash out. While “grandfathering” will solve some challenges, that could take thirty years or more. Even more difficult, is building a new police culture, as no one wants to see the integrated force devolve to the lowest common denominator (LCD).

My best guess, whether full or in part, the amalgamation will be under a command and control leader as there would be so many pressing day-to-to issues to deal with. This would also make it extremely difficult to even think about internal issues that exist in the present day. Neither would it be like Surrey where a new police force is being built largely from scratch.

Is there a way to avoid all these conflicts? There is and it is one that helps to bring forces together in common purpose while preserving the best of the individual parts. Before moving to that question, there are still dozens of local issues that need to be considered.

Note: The section numbering system from Part I, will be continued through each subsequent part.

4. The challenge of implementing change

Large departments like Metro Toronto, Montreal, Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Calgary, have a far more difficult time changing direction than do mid-size and smaller departments as in the range of Victoria, Saanich, Oak Bay, Central Saanich, etc. Everyone has watched as the largest amalgamated force in Canada, the RCMP, struggled to deal with issues that have dogged them for decades.

Canada, the RCMP, struggled to deal with issues that have dogged them for decades.

While Victoria/Esquimalt and Saanich, each with populations in the 100,000 range, outsize their Municipal partners in Oak Bay, Central Saanich, and those policed by the RCMP, there remains an opportunity to make major changes well short of amalgamation. If just Saanich and Victoria merged (200,000 population) or the entire region (350,000), it would not only mean a significant change for up to two-thirds of the population, it would mean a significant change for the majority of police officers. And, it seems likely, this change would not be in a positive direction.

It may well be that a regional model of shared services could be vastly superior to amalgamation and that this mixed model may provide a better means of assisting VicPD than offered by full out amalgamation. This will be explored in-depth in a later part of this series. Let’s now consider two amalgamations, one small and one large. First, the Victoria/Esquimalt merger of 2003, and second, the largest amalgamation to ever to take place in Canada, that of the RCMP. First, to Victoria/Esquimalt.

The following quote was taken from a Times Colonist article written ten years after that merger:

“The Victoria Police Department needs to fix its broken relationship with Esquimalt before it can convince Greater Victoria mayors and citizens that a single department is viable, officials in Saanich and Esquimalt said in response to a leaked VicPD regionalization report.”

“I’ve always said that if we can get our house in order in terms of Victoria and Esquimalt, then we are a model for those naysayers to look and say, ‘Yes, they can make it work,’ ” said Esquimalt Mayor Barb Desjardins, who has read Victoria police’s regionalization report, which was leaked to the Times Colonist.”

Now, five years on from that statement, and sixteen after the original merger, management of the two forces are no closer to harmony than they were at the time of the merger. What use was the merger if sixteen years later, things are still in a state of seeming (if not actual) chaos. Perhaps a large percentage of Esquimalt residents today might well prefer a return to a smaller force as in Oak Bay or Central Saanich.

Why are words such as “broken relationship” and a need to “get one’s house in order” even used to describe the problem? I think the challenges relate more to the basic policing culture of the two organizations. Over my thirty-year career, I worked with both departments on a number of cases and both exhibited similar characteristics in terms of their policing world view.

Of course, for Esquimalt, the fact they were a police-fire combination didn’t really work for either the police or the fire. There were just too many conflicts of interest, but because members received a substantial bonus for carrying out both jobs, that perk was not going to be given up easily.

When the divorce was finalized, and Esquimalt police members moved to VicPD, I don’t think anyone realized how difficult it would be to serve two masters even though both departments shared a similar culture. When speaking of those similarities, the first thought that comes to mind is ‘let’s get ready to rumble!” This attitude was completely opposite to the shared values of Oak Bay, Central Saanich, and, to a considerable extent, Saanich, where community service remains a core value.

6. Team Leader-Victims

Within the history of VicPD and, to some extent, Esquimalt after amalgamation, there is now a palpable sense of defeatism. It’s as if the woes of the world rested upon their shoulders and it hasn’t helped to have three outside Police Chiefs leave the force in disgrace between 1999 and 2017. The result, over the past fifty-five years, almost thirty-five years was spent with leaders who either did not practice an innovative forward-thinking style or became mired in issues surrounding disgraceful conduct. How did that set in place a model of competence and trust?

Check the following eight items, then consider whether you have heard one or more of these comments voiced by a VicPD Chief Constable, the Mayor, or other City Officials, a Chamber member, or a media outlet, on a regular basis over the past twenty years?

1. Blaming others for their problems (e.g. outsiders coming downtown to a party)

2. Blaming other departments and municipalities for not carrying their share of the workload.

3. Refusing to accept responsibility for many of the problems experienced.

4. Expecting others to feel sorry for them (a classic ‘victim’ response)

5. Focus on problems, yet complain incessantly about those problems without making a real effort to solve the core issues?

6. Imply or outright state that other departments are better resourced, have a lighter load and therefore have opportunities to do a better job.

7. Tend to reject constructive feedback.

The following quotes are taken from an October 15, 2011, Times Colonist article by Jack Knox in which Mayor Dean Fortin was speaking to a group of VicPD members led by Chief Jamie Graham.

Mayor Fortin: “I’m frustrated on behalf of the citizens of Victoria and Esquimalt, and I’m frustrated on behalf of (you) men and woman of the Victoria Police Department, who have been serving both communities so well.”

“It’s time to stop re-arranging the chairs and say which ship should go. Let’s take a look at regionalization. Let’s take a look at bringing in a Greater Victoria police force – one that can address these issues in a fundamental way. What’s the right thing for our citizens?”

That this the type of organizational blaming emanates on a regular basis from VicPD and seldom from Saanich, Oak Bay, Central Saanich speaks volumes about the basic culture surrounding the 0rganization.

It is an established fact that a Chief Constable and others having substantial control over a police department are responsible for setting the tone of that department. If they fail to inspire by example, fail to present workable solutions, or fall into a pattern of blaming others for all the problems, that attitude soon spreads throughout the entire force.

If the answer is ‘yes’ to even half of the eight comments above, you can’t help but think the senior administration of VicPD and others in the City of Victoria, might well benefit from some serious organizational counseling. Why? There is a substantial body of knowledge describing the challenges faced when groups within an organization adopt a victim mentality. When it originates at the top levels of administration, it is particularly deadly. There are several management firms in the business of helping organizations deal with such challenges. Following is a sampling of the characteristics of the Leader-Victim, referenced as The Primes.

Team Victim Mentality: The following quotes were collected from The Primes website: The simplest way to explain what has and is happening in the Victoria/Esquimalt PD is to read these comments.

“Leaders identify when groups operate from a sense of empowerment and a can-do attitude; effective leaders help victim-oriented groups regain their power, and help empowered groups sustain theirs. Being the VICTIM is much easier than being the LEADER.”

“In any conversation, groups move toward being LEADERS or VICTIMS. They talk either about things they can do or about what’s being done to them. Once this PRIME is distinguished, the group becomes directly responsible for tolerating victimhood. This awareness makes what once was easy to become suddenly unpleasant and intolerable.”

“Great leaders and high-performance teams listen carefully to the tone and direction of conversations. They can identify when a group begins to lose its power by complaining about things it can’t affect and blaming others for its own lack of effectiveness. There’s nothing to be gained by wishing that things we can’t control were different.”

“When you take on the biggest challenges facing your organization you’re in for tough times. Instead of collegial support, you run into fear of the unknown, mistrust, skepticism – and sometimes outright contempt.”

“Limiting the scope of discussions to that which you can control means taking responsibility and refusing to blame others for what they do “to” you. It can be exhausting, but it is highly productive.”

“The PRIMES are universal patterns of group behavior that outfit you to work with any group to solve any problem – especially the big ones.”

The fact a succession of Victoria Chief Constables and Mayors jumped on the amalgamation bandwagon over the past twenty years, has not helped. Some even went so far as outlining how the Victoria Police would divide the CRD into four districts as described in a secret report of a few years back.

I don’t have a copy but the Times Colonist provided a summary (Regional Police Force). Following is a graphic from that report. To have a Victoria Police Chief suggest how he and his force would reconfigure the region is presumptive beyond words. The Chief even made it clear in the district numbering system, where the power would reside. You can be certain that power won’t include View Royal, Esquimalt, Oak Bay and most of Saanich even though they are included as part of District 1.

Regionalization Report by VicPD

Perhaps the current VicPD Chief, a force insider for a change, can turn things around, but to do so he and his close advisers along with the Police Board, City Council and members of the business community, need to stop complaining and get on with the business helping their members move along a path to success rather than always having them stare into the abyss of failure.

There are a great number of things they can do to emphasize the positive rather than a negative and they need to be seen as moving forward rather than standing still or moving backward into smaller and smaller defensive circles.

By most standards, Victoria is a small, relatively crime-free city, surrounded by peaceful neighbours willing to help, but not willing to throw all their policing eggs into the Victoria basket. No one needs that much negativity as it won’t go away simply because forces amalgamate as evidenced by the Victoria/Esquimalt merger. More will be said on how this might be solved in the upcoming parts of this series. For a moment, let’s now take a quick look at the RCMP.

7. Amalgamation and the RCMP

Many may not realize it, but the RCMP represent the largest single amalgamation of police forces in Canadian history:

“In 1919, Parliament voted to merge the Force with the Dominion Police, a federal police force with jurisdiction in eastern Canada. When the legislation took effect on February 1, 1920, the Force’s name became the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and the headquarters moved to Ottawa from Regina. The RCMP returned to provincial policing with a new contract with Saskatchewan in 1928.

From 1932 to 1938, the RCMP took over provincial policing in Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, nearly doubling in size to 2,350 members. The years following World War II saw a continued expansion of the RCMP’s role as a provincial force. In 1950, it assumed responsibility for provincial policing in Newfoundland and absorbed the British Columbia Provincial Police in the same year.” (History of the RCMP)

While I won’t go into detail, the RCMP, the most storied police force in Canada, continues to be plagued by scandals of one sort or another. A post written a few years back, titled, Oversight of the Poice and Security Services, (reference Part 4), provides a summary of some of most egregious crimes committed, all in the name of keeping our communities and country safe. Further discussion on this point is contained in footnote (2).

Part 1 of this series and section 4 above, point out how bringing about change becomes more difficult as a police force grows in size. The RCMP is many hundreds of times larger than any other police force in Canada and the internal challenges faced as the force grew, have increased every step of the way. The recent billion-dollar settlement with the rank and file members speaks to the depth of the challenge. The one bright light on the horizon and one that may serve to rein in the absolute control held by the senior ranks is the formation of a police union.

8. Closing Comments

Across the broad spectrum of police members in Canada, the vast majority are well-trained and trying to do the best they can in sometimes trying circumstances. Even in the criminal actions that infected some sections of the RCMP in the 1970s, it was the rank and file who were blamed when, in fact, it was the senior leaders, right to the office of the Commissioner who sanctioned those actions. A member who didn’t walk lock-step under the instructions given (or intimated) would carry a DNP tag (Do Not Promote) for the rest of their career. Let’s hope senior members of the force do not stray into spying and investigating their own Union as they did so many others in the past.

During my career, I worked with many RCMP members whose careers became sidelined, and more than a few quit, simply because they spoke out about force practices. You may have noticed — the flow of members from the RCMP to City and Municipal forces are constant, and it’s more about freedom from the tyranny of rank than it is about money. The flow the other way? Almost non-existent.

Harold McNeill

Det/Sgt Oak Bay Police (Ret)

Upcoming: In Part III the focus will move to the process of change – how it was accomplished in the past and what needs to be done today. This opening paragraph:

“In every discussion about finance and staff reallocation, you can rest assured Victoria, Saanich, and every other medium and large department across Canada, fritter away hundreds of millions of dollars each year. They do so by maintaining enforcement regimes that are next to useless in terms of utilizing the full value of highly trained and experienced police officers.”

Footnotes

(1) A Short History of Policing in the CRD. (1960 – 2019)

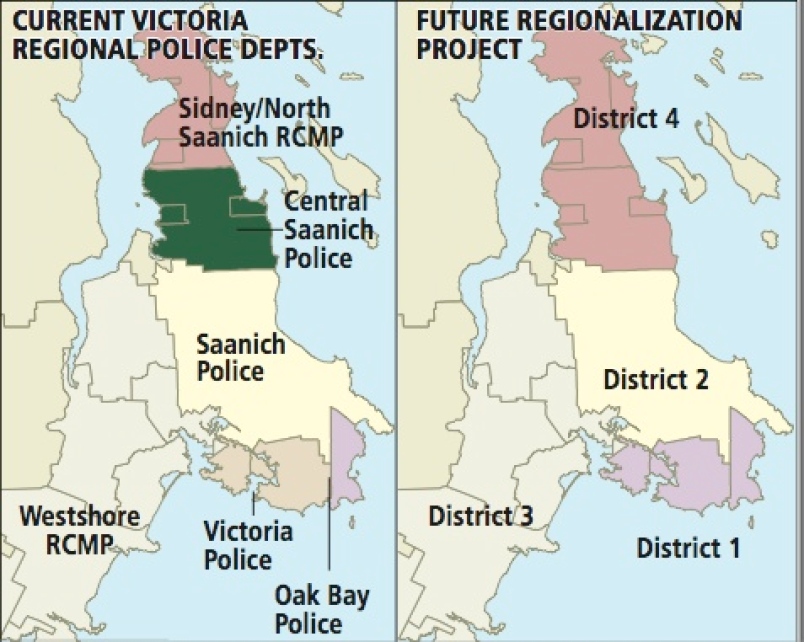

This photo was taken about a year after completing my recruit training in Vancouver.

This footnote digs deeper into the characteristics of the various departments and the paths they followed to the present day. It may seem I go back some distance in time, however, it is my submission that the characteristics an organization develops are largely defined by the people who held the reins of power in the past.

In this sketch, you are asked to remember that following the end of World War II, and the Korean War, police departments justifiably recruited heavily from among veterans. These were good men (and they were all men), however, some were steeped in the strict rank structure of military organizations on a war-footing. There was no doubt many would carry their military training and bearing into the police departments they joined.

When I joined the Oak Bay PD after completing my recruit training at the Vancouver PD Academy, the Police Chief was a 6″ 4″, 265 pound Highland Games tabor thrower with the chest, arms, and shoulders of a gorilla. More importantly, he was a retired Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) with a baritone voice that could shake the confidence of even the strongest amongst us. This from Wiki:

“The RSM is primarily responsible for maintaining standards and discipline and acts as a parental figure to their subordinates and also to junior officers, even though they technically outrank the RSM.”

I’m not sure about the parental figure unless you had a very stern father. The only words used with the Chief was “Yes, Sir! No, Sir!” and when he told you to jump, you might be permitted to ask “How high, Sir?”

Our police office was furnished from a war surplus store, it was cramped and paper clips were individually counted in the supply room. Two police cars were large station wagons that could double as ambulances and there was still an air raid siren near Foul Bay Rd. and Henderson, that was tested once a month as a part of the Cold War preparations. There were no walkie talkies, so when you left the car, it was equipped with a decoder by which dispatch could blow the car horn if you were needed.

Our uniforms were near war surplus with a notoriously dangerous Second World War sidearm, the Webley top-break, as dangerous to the user as those in the near vicinity. More than one shot was accidentally fired in police locker rooms around the country. The gun holster was held by equally dangerous harness called a “Sam Browne” (group photo above). Let some drunk grab that cross-strap and you nearly had to shot the (so.) to get them to back off.

Our neckties were still placed under our shirt collar and tied at the front. It took a few years of police union activity to convince management that the tie was just as dangerous as the Sam Browne strap if a belligerent individual decided to grab hold. Our boots were a bulk purchase issue, ill-fitting and the leather soles as hard as a rock. More than one police member eventually left the force on compensation or disability because of a fallen arch or other foot and leg problems. As for wages, the fact every Constable, had a second job just to make ends meet, tells the story.

If Oak Bay members thought their conditions were primitive, the Victoria force was in far worse shape. They had moved into their Fisgard Street HQ in 1918 and by the mid-1960s it was doubly cramped and massively out of date, yet it would be their home for the next thirty years. At least in Oak Bay by the 1980s, the office was completely renovated into a form similar to that which exists today. If you have a moment, drop by the Oak Bay office and have a look. For a small police force, it is as welcoming and professional as you will find anywhere in the country. It is the quintessential community police office. Now back to the VicPD.

In addition to all the space needed for the members and civilians, the VicPD building held at least one full-time courtroom, a jail, a fines payment counter and a ground-level parking garage into which they stuffed as many patrol cars as possible. It was in that courtroom the first murder trial in which Constable Al Campbell and I were the lead investigators, was held before Judge William Osler, one of the few lay judges to sit on the bench in modern times. It’s somehow hard to imagine having a murder trial in the middle of an active police office.

Esquimalt, in turn, was in even worse shape than Victoria as their office was no more than a basement storage area and the equipment was so out of date, many of their case files were still being handwritten. When others were slowly changing to IBM Selectric typewriters, and the incipient stages of computing, Esquimalt still used phones with rotary dials.

As I recollect, Saanich always fared better than everyone else in terms of building and equipment. I think they were sharing a building with the main hall of the Fire Department (as did Oak Bay). While the building was fairly modern by the standards of the day, it was subject to a number of renovations over the years.

Real change for Oak Bay began in the late 1970s with the departure of the RSM Chief at which time an outside Chief appointed. This change was also accompanied by a rank structure change and by the end of the 1970s, early 80s, the building had been completely renovated and much of the administrative and operational records systems had been updated (as outlined in a footer of Part 1).

In Victoria, an RCMP Staff Sergeant (almost the same personality as the Oak Bay RSM) with thirty years experience in the RCMP (as I recall that was his service when he retired from the force), was appointed Chief in 1964. His mandate was to address some of the disciplinary challenges the force experienced between the end war and the early 1960s. He was strict disciplinarian, steeped in the spit and polish traditions of the RCMP, and he fulfilled his mandate with a dedication that only an RSM or RCMP S/Sgt. could muster.

As his mandate was to ‘clean things up,’ modernization was not in his lexicon. He firmly held the reins for the next sixteen years and this delayed any real change until a new Chief entered the office in the early 1980s. Even at that, the force struggled to regain a modern footing and it was not until the force was taken over by a full team of insiders who were promoted from within the ranks, that the force moved forward and even gained a brand new home they now occupy on Caledonia Street.

That progress ended in 1999 after which no less than three outside Chief Constables were appointed over the next seventeen years and each one ended up leaving the force in disgrace. It was a tragically difficult time for Victoria as their leadership seemed constantly consumed by scandal. The fact that one of those Chief Constables had left the Vancouver Police Force, just one step ahead of being brought up on several misconduct charges while he was the Chief is another of the great mysteries of Victoria Police Chief selection process.

As a general observation, I would say Victoria Police very likely would have thrived had there been a complete package of mentoring from within the ranks. The force certainly had dozens of talented men and women, but they were never groomed for the position of Chief and the Police Board never seemed to think that was a priority.

By contrast, the Saanich Police have consistently prepared members to take on leadership roles. As far as I know, they have never appointed an outside Chief Constable and as a result, the force has thrived. All the Chiefs either retired or otherwise left the force with glowing recommendations. One influential Saanich Chief in the early years left to set up the now hugely popular Criminal Justice Program at Camosun College. And, as a minor aside, one who recently retired, spent the early years cutting his policing teeth as a Reserve Police Officer with the Oak Bay PD?

As for smaller departments of Oak Bay and Central Saanich, the appointment of inside Chief Constables can be problematic, as the selection pool can be shallow. Even at that, Oak Bay has had a solid mix of inside and out and over the past fifty-five years and they have all been good choices.

(2) RCMP in the 1970s.

That the crimes were committed just twenty years after the force assumed control of the majority of Provincial Police forces across Canada, speaks to the challenges of maintaining accountability in large police organizations. You might well state, “well that was back in the 1970s, things have changed since then.” Yes, a lot of things have changed, but you might take note the Victoria/Esquimalt merger is now in its sixteenth year and the issues are nowhere near being sorted out.

You might also wish to track the challenges faced by the RCMP from 2000 to the present day. In that, you will see a history of conflict and in the past few years, British Columbia and Alberta have both toyed with the ways and means of backing away from the force. Surrey is currently in the midst of that process.

Also, if you pay even casual attention, you will note a number of media reports in which the RCMP, CSIS, and CBSA are again tracking towards committing crimes and abuses of power as occurred back in the 1970s. The most recent case in this area was documented in an article, Conspiracy to Bomb the BC Legislature. Again, this abuse of power was done in the name of keeping our nation safe from terrorists.

As a result, the RCMP continues to be under immense pressure to implement reforms designed to bring about systemic change. Central to this is implementing independent oversight, as well as legislating the right of the rank and file to form a police federation that can bargain for better wages and working conditions.

Part of the new Federations mandate will most certainly be advocating for the rights of all rank and file members. It is noted in the news of July 12, 2019, the National Police Federation, won the right to move forward with collective bargaining with the Treasury Board. This is a change of monumental proportions for the RCMP.

While the path to reform will be difficult and take many years, at least some of the pressure is now removed from individual rank and file member, whistleblowers, investigative reporters, the courts, and, in recent decades, lawsuits brought forth by female members. While Unions and Associations have taken some heat for being greedy, it is also clear that much of the social change in terms of workers rights in Canada and around the world was brought about by these grassroots organizations.

This change may certainly help Surrey move toward a city force although it is expected the RCMP will fight the move at every stage. If Surrey succeeds, it could well open the floodgates across Canada as more provinces, cities, and municipalities move away from the RCMP.

Strangely enough, having the RCMP move away from this extreme mix in policing, might well help the force to become that for which it was originally intended, a Federal Police Force not unlike the FBI.

hdmc

(3) List of past and current Chief Constables in the local PD’s. This will be included after the list is complete.

(436)

Trackback from your site.