Posts Tagged ‘Melvin Wheeler’

Cold Lake High School Years: The Journey Begins

Early in the 1950’s the largest RCAF Station ever constructed in Canada was taking shape in Alberta. The small, remote, communities of Cold Lake and Grande Centre, that grew ever so slowly over the first fifty years of the century, would be shaken to their foundations as they struggled to come to terms with a massive influx of workers and their families. Our family was one of the many seeking to find their way.

Dear Reader,

For the several months, I struggled with how to write this post about our return to Cold Lake. To this point, it was easy to tell the stories as they were all generally positive. Even though our family was constantly on the move over the twelve years until this story, everything was relatively stable on the home front. All that changed in 1953 after arriving in Cold Lake and it continued in one form or another until our Dad passed away suddenly in 1965. While I will not dwell on the very difficult parts, and there were many, I felt compelled to express the feelings that enveloped me during those tumultuous years as a means to better understand myself and, perhaps, as a message to others.

I rather expect at least a few of my school friends shared similar experiences and might even take solace in knowing they were not alone. The background to this story is alcohol abuse, but it could easily have been any of a dozen other things that cause family units to fracture – drugs, infidelity, mental illness, etc. Children and teenagers, in particular, are vulnerable when this happens and need to know they are never alone, that even when things get really bad, the future can still hold a great deal of promise.

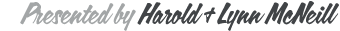

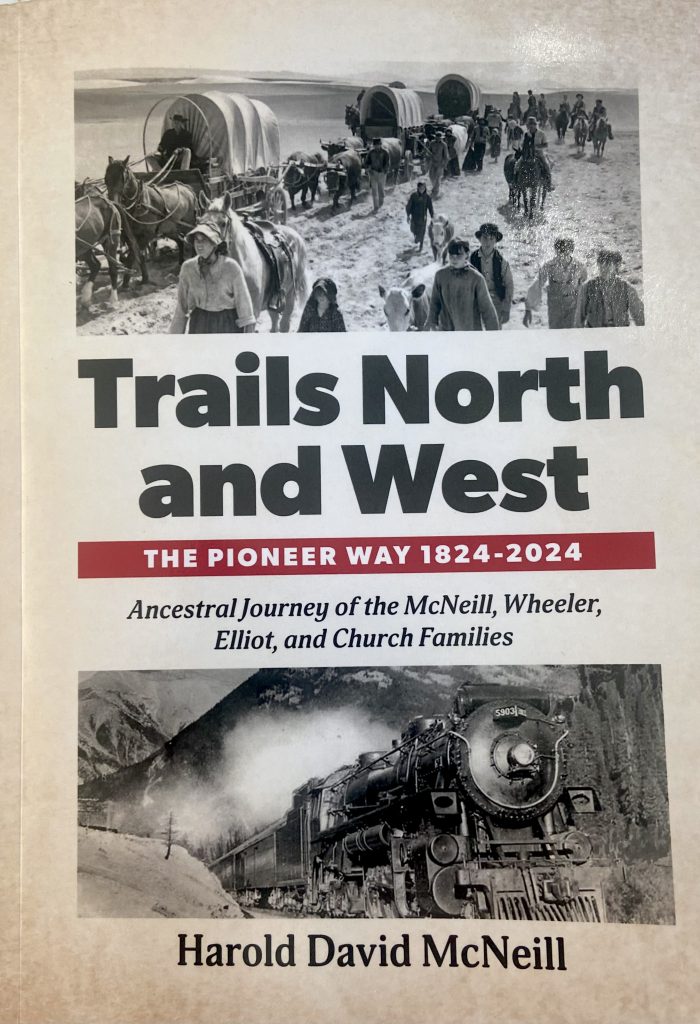

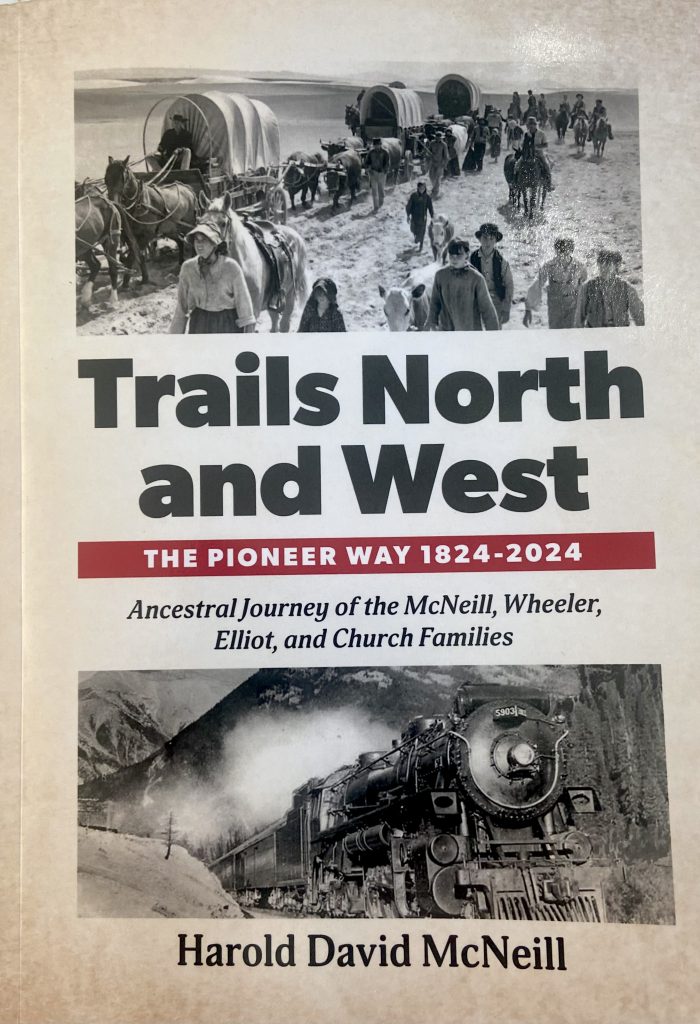

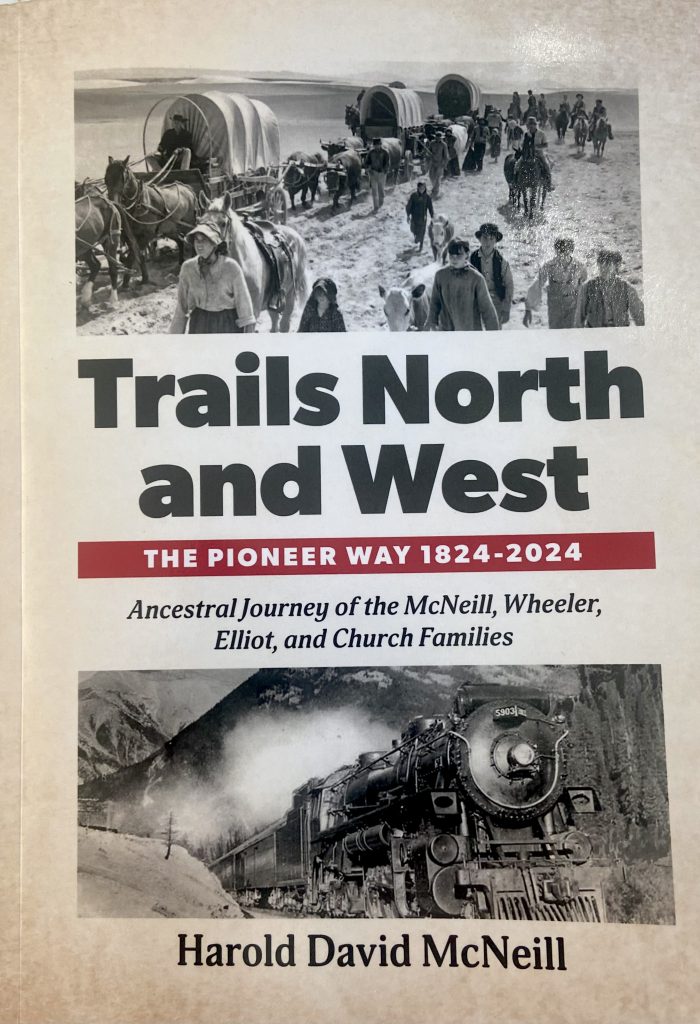

The full story, including this Chapter, is now in book form;

This Book is available from

Kindle Direct Publishing

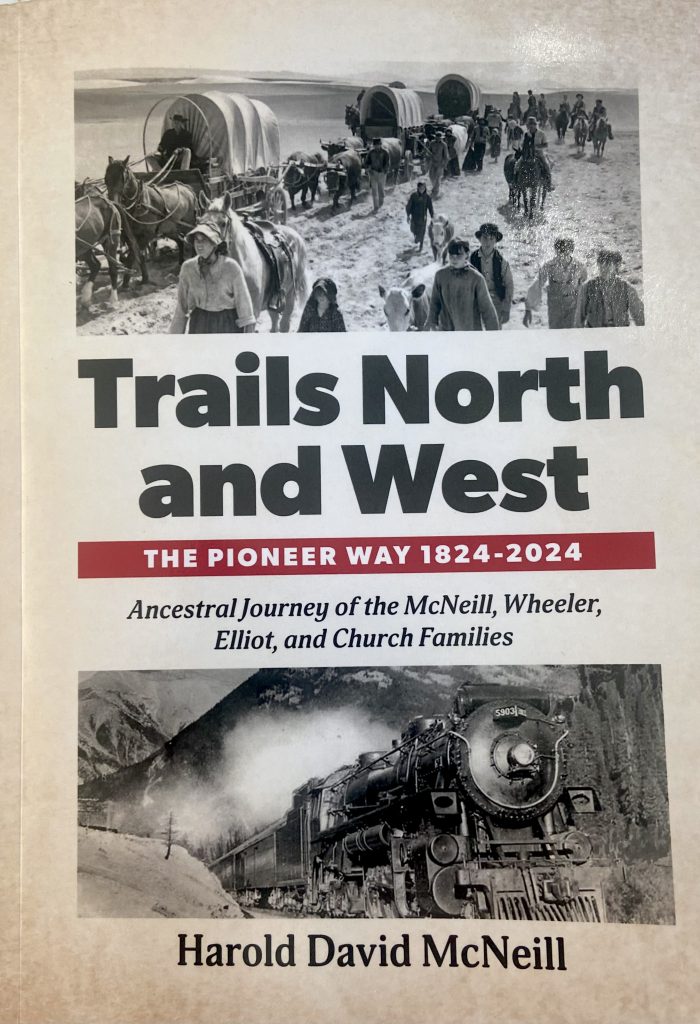

Book 2 -Trails North an and West: The Pioneer Way 1824-2024 is now available from Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) You can search by book title or author name. A preview of the first seventeen pages is provided (link on bottom left on the KDP order page). The preview also includes the Table of Contents.

Note: When ordering four or fewer books, they will be printed and shipped within Canada. An order of 5 or more books may be printed and shipped from the United States. Postage is included in the purchase price when ordering from either country.

If you are thinking of sending books as gifts to others, you may consider having those books mailed directly to the recipient(s), by Amazon, at time of ordering. In this way, you would avoid Canada Post fees which currently run about $20.00 (plus tax) for one or two books, if enclosed in a single mailer.

For more background information on the story, go to the lead story on this blog.

Cheers,

Harold

End Comment

While life was often tough at home when things went sideways, it was all about learning to handle life. How we respond when life throws a curve is what makes us stronger, not weaker. We all need to work for the best and learn to deal with the bad as it comes along. Mom is an excellent example of how she motored her way through the difficult times. Dad, in his own way, also passed along his best as you will noted in the previous stories in this series.

In the next part of the Junior and Senior High School series, I will zero in on more of things that made the school years so special – sports, cars, girls, liquor, parties, and, yes, a little study (not necessarily in that order, but pretty close).

As I write those future stories, I will draw upon the experience of family and friends while being sensitive to their privacy.

Harold

Further Links:

(Link here to additional photos that accompany this story)

(Link to Chapter 17, Cold Lake High 1955 -1960)

(3712)

Harlan: A Tragic History – Chapter 2 of 6

Photo (Frog Lake Memorial): One man who died was the John Delany, the Grandfather of my Aunt Hazel (wife of my mom’s brother Melvin Wheeler), all part of the interesting history of our family. Note, many of these historic signs still denote the event as a Massacre in the midst of the Northwest Rebellion. Little mention is made at these historic sites of the attempt by an “Indian Agent” follow the “letter” of the laws passed in Ottawa, to starve the local bands into full submission to his wishes.

The full story, including this Chapter, is now in book form;

This Book is available from

Kindle Direct Publishing

Book 2 -Trails North an and West: The Pioneer Way 1824-2024 is now available from Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) You can search by book title or author name. A preview of the first seventeen pages is provided (link on bottom left on the KDP order page). The preview also includes the Table of Contents.

Note: When ordering four or fewer books, they will be printed and shipped within Canada. An order of 5 or more books may be printed and shipped from the United States. Postage is included in the purchase price when ordering from either country.

If you are thinking of sending books as gifts to others, you may consider having those books mailed directly to the recipient(s), by Amazon, at time of ordering. In this way, you would avoid Canada Post fees which currently run about $20.00 (plus tax) for one or two books, if enclosed in a single mailer.

For more background information on the story, go to the lead story on this blog.

Cheers,

Harold

Link to Next Post: Snakes

Link to Last Post: Old School House (First of Part IV)

Link to Family Stories Index

Link here to photo’s of Frog Lake adventure: LINK HERE

Also, a note by Phylis Wicker Glicker

Hazel Martineau [Wheeler] daughter of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau b. Oct. 18, 1875, St. Boniface, Manitoba, Canada, and Margaret Delaney b. Nov. 30, 1885, Frog Lake, Alberta, Canada. Adrien is the son of Herman Martineau b. Brittany France mar. (1) Annie Macbeth (2) Angeline LaBelle. Herman Martineau is the son of Ovit Martineau b. Brittany, France. I have just begun researching the Delaneys and Martineau”s so I don’t have much. But I would love to hear from you and share what I have. I was married once to Frank Martineau, grandson of Adrien Louis Napoleon Martineau and would love to learn about Margaret Delaney’s family for mine and my children’s sake.

Email: pwicker@telus.net

(4234)

Marie Lake: Crash on Highway 28 – Chapter 7 of 11

Family Photos via Mom’s Photo Keepsakes (July, 1948). I always remembered this photo and by good fortune on January 2, 2016, it magically appeared in a photo album my sister Dianne McNeill had preserved. It now stands as the lead photo in this story of this accident that nearly killed our father, Dave McNeill and injured several others. The photo was taken in the Cold Lake Hospital just before Dad was transferred to Edmonton for emergency surgery.

The full story, including this Chapter, is now in book form;

This Book is available from

Kindle Direct Publishing

Book 2 -Trails North an and West: The Pioneer Way 1824-2024 is now available from Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) You can search by book title or author name. A preview of the first seventeen pages is provided (link on bottom left on the KDP order page). The preview also includes the Table of Contents.

Note: When ordering four or fewer books, they will be printed and shipped within Canada. An order of 5 or more books may be printed and shipped from the United States. Postage is included in the purchase price when ordering from either country.

If you are thinking of sending books as gifts to others, you may consider having those books mailed directly to the recipient(s), by Amazon, at time of ordering. In this way, you would avoid Canada Post fees which currently run about $20.00 (plus tax) for one or two books, if enclosed in a single mailer.

For more background information on the story, go to the lead story on this blog.

Cheers,

Harold

Link to Next Post: Link to On Thin Ice

Link to Last Post: Link to My Best Friend

Link to Family Stories Index

(1805)

Birch Lake – The Blizzard of ’41 – Chapter 1

Photo (Saskatchewan Farm Life): In the early years of living on the farm in Saskatchewan, winter blizzards could arrive suddenly and last for days. Travelling in such such conditions could be a dangerous affair.

Link to Next Post: A New Beginning

Back to Main Index

Deep Winter, 1941: A Baby is Born

Just after ten in the morning, the pain struck, causing the expectant mother to double over. She grabbed the kitchen table to keep from falling, and as the pain eased, she lowered herself into an easy chair near the log fire. Home alone, two miles from the nearest neighbour, ten from the village of Glaslyn, and forty-five from the hospital in Edam, she was frightened. With no idea what time her husband might return, she considered walking to the nearest neighbour, something she did many times. But now, amid this January blizzard, with its bone-chilling cold, and drifting snow, that was out of the question.

The full story, including this Chapter, is now in book form;

This Book is available from

Kindle Direct Publishing

Book 2 -Trails North an and West: The Pioneer Way 1824-2024 is now available from Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) You can search by book title or author name. A preview of the first seventeen pages is provided (link on bottom left on the KDP order page). The preview also includes the Table of Contents.

Note: When ordering four or fewer books, they will be printed and shipped within Canada. An order of 5 or more books may be printed and shipped from the United States. Postage is included in the purchase price when ordering from either country.

If you are thinking of sending books as gifts to others, you may consider having those books mailed directly to the recipient(s), by Amazon, at time of ordering. In this way, you would avoid Canada Post fees which currently run about $20.00 (plus tax) for one or two books, if enclosed in a single mailer.

For more background information on the story, go to the lead story on this blog.

Cheers,

Harold

(3356)