Changing the way police do business (Part III)

Chief Del Manak, VicPD. A good man caught between a department with a problematic past, and a future filled with uncertainty. One thing is certain, the future will be filled with change whether it comes by choice, by chance, or by force. All police agencies have a choice, they can either resist or they can embrace!

Part I, Police solidarity and the push for amalgamation.

Part II, Comparing differing police cultures

Part IV The integration of police services

Link to CBC Podcast: Policing in the CRD

Contact: harold@mcneillifestories.com

(When reading this series it is recommended you start with Part I as each part builds towards the next.)

Part III The past as a guide to the future

4. Introduction.

No matter what the future brings, in police budget discussions money is seldom the real issue. In this, you can rest assured every medium and large department across Canada fritter away hundreds of millions of dollars each year. They do so by maintaining enforcement regimes that are next to useless in terms of utilizing the full value of highly trained and experienced police officers. What should stay, and what should go? These are the hard decisions that every police administrator must make and this can best be done by embracing the conflicts that come with change.

For small municipal departments and RCMP detachments, the issues are less critical as police members are generalists and, as such, their duties encompass the full spectrum of policing. They embrace the very essence of the Peelian Principles, where the Chief of the department might well end up on an emergency call with a Constable. However, the reality is, as departments grow in size through population expansion (e.g. the West Shore) or through amalgamation (e.g. Victoria/Esquimalt), the roles coalesce into increasingly specialized fields (e.g. patrol, traffic, administration, emergency response teams, detectives, with special units in fraud, homicide, robbery, cybercrimes, etc.).

Go to Toronto or look at their org chart, to get some sense of just how specialized they have become. Where is there room left to stay connected to Torontonians? (Toronto Org Chart, page 18ff). Scan the left two-thirds of the chart (Administrative and Corporate) then consider how much of the force is gobbled up by services that never touch the street! There is considerable literature indicating there is good evidence to suggest that “medium-sized police services (i.e. those policing about 50,000 inhabitants) are more successful in dealing with crime and operational costs than much larger regional services.” (link)

As discussed in an earlier part of this series, the efficiencies of size top out when departments service populations of around 50,000. What gets lost in the process of growing beyond that point is the ability to find the ways and means of staying connected to the community in positive ways (e.g. the quintessential beat cop, school and community liaison, etc.).

While some argue merging forces will reduce costs and improve efficiencies, all you need do is make a quick estimate of the current costs of policing in the city and municipal forces across Canada (large and small) to see that isn’t true.

You can do a rough check by multiplying the number of sworn members by $200,000. By doing that, you will arrive at a number that is within +/- 10%, of the posted budget of every police department, in Canada. The $200,000 figure was taken from the GTA (Greater Toronto PD) as that is one of the largest city amalgamations of police in Canada and if amalgamation produces efficiencies of scale, Toronto should be the most efficient and cost-effective in Canada. It is far from being either. Their budget is now $1 billion for 5000 sworn officers. Of course, there will be outliers in these figures, as that is true on every bell curve of many samples. Footnote 1, provides the calculations for policing budgets in BC and select cities across Canada.

While most police dollars are effectively spent, you need only explore traffic law enforcement to see how waste is built into the system. In general, police forces across Canada typically over-enforce traffic laws in ineffective ways and under-enforce in effective ways. While some provinces, cities, and towns are taking steps to correct this anomaly, progress is slow. The challenge of traffic enforcement will be more fully explored later in this article.

Part of the reason for the slow progress lies in the ideological, but the major portion remains in the form of resistance to change as exhibited by police administrators and unions alike. Medium and large police forces, like every other large enforcement agency (e.g. CSIS, CBSA, RCMP), work hard at building the size of their organization as the prime means of meeting challenges, rather than looking for effective ways of making them smaller and more effective.

This part of the series explores these matters both historically and in the present day. While the focus will be on the CRD and British Columbia, similar considerations apply across Canada.

5. Examples of past reforms:

A. The BC Sheriff Services

Until 1974, police members carried out the majority of duties now performed by the British Columbia Sheriff Service. The use of police officers in and around the movement of prisoners, court services and security, criminal warrant execution, document service, and dozens of other duties, became increasingly untenable as the court system grew. It was a specialized service the police were ill-prepared to carry out as members were rotated in and out of courts on an ad hoc basis.

It was a difficult transition but when finally completed and things settled down, everyone wondered why the change hadn’t taken place years earlier. Today, everyone would think it insane to  amalgamate the Sheriffs Service back into the police. Sheriffs now carry the same powers as peace officers as regards to the enforcement of federal and provincial laws throughout British Columbia.

amalgamate the Sheriffs Service back into the police. Sheriffs now carry the same powers as peace officers as regards to the enforcement of federal and provincial laws throughout British Columbia.

Through this same period, as external and internal demands increased, and tasks became more specialized, much of the work of dispatch, record keeping, and dozens of other clerical and administrative duties were fully transitioned to civilians who now comprise about two-fifths of every police force.

Private Security Agencies

The same transitions were taking place in street operations when private security firms began to provide full-time service in malls and at dozens of other locations where police members, both on-duty and off-duty, once picked up these special assignments. It was a tough one to let go as it offered a very good return to police officers for carrying out what many considered to be light duty. Today, private security personnel are visible throughout the community and at many public events.

B. Reserve Police Officers

It was also during this period, Reserve Police Officers were phased into service and soon become a valuable asset in every police force. Again, there was considerable resistance in the beginning, but once accepted, reserve officers began “accompanying police officers on patrol, assisting at community events, presenting crime prevention strategies in schools and at other locations, conducting traffic control, as well as foot or bike patrols in public parks and similar areas, and participating in search and rescue operations, and at parades and ceremonial events.” A recently retired Saanich Police Chief, Mike Chadwick, cut his teeth as a Reserve Officer with the Oak Bay Police.

C. BC Ambulance Service

Considerable attention is currently given to the number of calls related to mental health and other medical emergencies with opioid overdoses sitting near the top of the list. There is no question it is a crisis that needs attention but a few moments to reflect back to 1974.

It was that year the BC Ambulance Service was formed. Until that year the primary service was provided by a mixture of volunteer ambulance brigades, fire departments, funeral homes, and private operators, with police providing primary backup on almost every call for service.

year the primary service was provided by a mixture of volunteer ambulance brigades, fire departments, funeral homes, and private operators, with police providing primary backup on almost every call for service.

Today, BC Ambulance is among the largest Emergency Medical Services (EMS) provider in Canada and North America. The fleet consists of more than 500 ground ambulances operating from 183 stations across the province along with 80 support vehicles. BCAS provides inter-facility patient transfer services in circumstances where a patient needs to be moved between health care facilities for treatment.

Today, the number of professionals operating that service across BC numbers just under 5000. Even with that 5000, it is clear a present-day crisis involving the mentally ill and those suffering drug overdoses, is again stretching the emergency service providers beyond the breaking point.

Police Recruit Training

Another important transition was made when the training of all police officers and many other agencies in BC was slowly transferred to what is now known as the Justice Institute of British Columbia (est. 1978). The programs now include dozens of specialized fields up to and including a Bachelor of Law Enforcement and other graduate certificates presented to  over 30,000 registrants each year. In Victoria, the Justice Institute had its nascent beginnings at Camosun College (formerly known as the Institute 0f Adult Studies), under the leadership of John Post a Chief of the Saanich Police who took early retirement to kickstart the program.

over 30,000 registrants each year. In Victoria, the Justice Institute had its nascent beginnings at Camosun College (formerly known as the Institute 0f Adult Studies), under the leadership of John Post a Chief of the Saanich Police who took early retirement to kickstart the program.

Prior to that, training in the Lower Mainland was centered in the Vancouver Police Academy, then located at the PNE grounds. For police in the Captial Region, I think the Saanich Police operated their own program under Chief Post, while Victoria sent recruits to Vancouver. Constable Barrie Parker and I were the first recruits from Oak Bay assigned to the four-month Vancouver PD program along with recruits from Esquimalt and Victoria.

By-Law Enforcement Officers

In another significant role transfer, most urban and suburban centres, small towns and semi-rural communities, now employ by-law and parking enforcement personnel to carry out duties once performed by police officers.

While it took some serious negotiating to accomplish these changes, all are now accepted as being the best way to free up police officers to perform duties requiring extensive training and on-street experience.

Yet, there remains an area of traditional police work that consumes thousands of hours and significant sums of money in an extremely inefficient manner, that of traffic law enforcement. In every police agency across Canada, Police Chiefs and their delegates, regularly assign hundreds of highly trained, experienced police officers to traffic divisions.

Ticket books in hand, these enforcement officers and squads spread throughout the land in search of offenders. While you won’t find a standing order about how many tickets should be issued, you can rest assured a traffic cop falling below a certain threshold will soon be having a chat with his or her Sergeant. Over my thirty years of policing in and around the Greater Victoria area, I could point to dozens of examples of how inefficient our system of traffic law enforcement was then and continues to be in the present day.

Note: In this discussion, all duties related to the investigation of serious accidents causing death and injury as well as the detection and prosecution of criminal actions such as impaired driving, criminal negligence, hit and run, and dozens of other serious offences involving motor vehicles as well as other means of transport on our highways, would remain in the hands of the police.

5. Traditional Traffic Law Enforcement: The relic of a bygone era

On July 5, 2019, a Victoria News headline read: “Saanich Police Issue Drivers over 100 tickets in one  day: The Traffic Safety Unit (TSU) focussed on distracted driving and speeding across the city”.

day: The Traffic Safety Unit (TSU) focussed on distracted driving and speeding across the city”.

What do you suppose the impact of that blitz was in terms of changing general driver habits? Probably zero? More likely, the majority who received a ticket, drove away feeling irritated at having been picked off out of hundreds who commit the same offence each day. They were just the unlucky ones who happened by at that particular location at that moment in time. There may be a slight general deterrence effect, but it would have such limited value as to be negligible. First, the chances of getting caught are slim and, second, the vast majority of drivers generally abide by traffic laws. Footnote (2) provides an anecdotal observation of traffic on the Patricia Bay Highway.

This brings up the point of when, where and how, should police enforce the traffic laws, and, is it necessary for police to even carry out the type of enforcement required in the present day where traffic volume in many cities can bring things to a standstill.

A. Observing traffic patterns

It always seemed reasonable that if police were going to undertake some type of enforcement action like issuing traffic tickets, there should some checks and balances to determine whether the approach was effective. Traffic flow, speed, and accident rates are areas in which research can be easily conducted. Do you  suppose the Saanich TSU even considered whether what they were doing was having any effect beyond some short term deterrence as might be the Oak Bay case in this cartoon?

suppose the Saanich TSU even considered whether what they were doing was having any effect beyond some short term deterrence as might be the Oak Bay case in this cartoon?

Cartoon (Raeside): Officer McNeill in hot pursuit along Oak Bay Avenue (c1970)

In setting up controlled situations to check the value of enforcement, the results were clear, both in the ad hoc studies and in the literature. Traffic cops could spend their entire career issuing random tickets by the tens of thousands and it would not make the slightest difference. What it might well accomplish is bringing in piles of cash. Here’s an interesting story from Winnipeg which aired on CTV’s W5, from 2013: Are Police Handing out tickets to meet quotas?. It’s bad enough having a quota system, but a quota based on income generated would, in similar circumstances, constitute discreditable conduct by those having sanctioned the practice. Does it happen in B.C. today? I don’t know, but suspect in one form or another, it does.

B. Integrated Road Safety

While the BC Integrated Road Safety Units (IRSU), appears to be more selective by choosing “high incident locations”, even in that, the effort is doomed to failure as it only means targetting some locations on an intermittent basis (3). The IRSU has one hundred officers spread across the Province (Lower Mainland, Fraser Valley, Vancouver Island and in the North and Southeast interior districts). I don’t wish to seem overly critical, but that number of officers couldn’t even make a difference even if they were all moved to the Lower Mainland or the Island. It’s a public relations effort. You can count traffic tickets by type, and the amount of income brought in, but that’s about it.

If traffic divisions want to make a real difference, they need to be very specific in their planning, they need to set goals, and they need to develop strategies to meet those goals. Finally, they need to conduct ongoing studies to determine whether what they are doing is having the desired long-term effect. If they took the time to read the literature, they would realize traffic enforcement in its traditional form is not having any appreciable effect. To cut to the chase, large police departments need to get out of the business of general traffic law enforcement.

The only parts that need be retained, as mentioned above, is the enforcement of criminal offences (e.g. impaired driving, dangerous driving, hit and run, etc.) as well as investigating accidents involving injury and death. The use of roadblocks may have some limited value in detecting offences such as impaired driving and non-moving violations (insurance, licencing, etc.) but even in that, there is no need for a large police presence.

The majority of the day to day traffic control can be shifted to technology and specialized units charged with developing and implementing campaigns designed to change driver behaviour. There is clearly a lot of money in the system as vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death and injury in British Columbia with costs totaling nearly $9 billion a year. If as little as a five percent reduction in crashes could be achieved, that would produce $450 million in savings. With that kind of money, some serious targetted programs could be initiated. Link here for a discussion on auto insurance rates in British Columbia. When

I don’t know what percentage of area police budgets is dedicated to traffic law enforcement, but I suspect it’s significant. Just as Sheriffs were brought in to take over a number of police duties, that same transfer of power must take place in police traffic divisions. If they are to be kept under the purview of the police, it needs to be done in a manner that includes persons skilled in technology and trained in doing research and analysis of various programs put in place. Also, the goals must relate to reducing accidents by changing driver behavior, not as a means to raise money to pay for the service.

C. Prevention of traffic crashes (literature)

One of the classic studies conducted in British Columbia back in the 1970s was a volunteer one in which drivers using the Trans Canada Highway between Abbotsford and Hope were requested to leave their vehicle headlights on during daylight hours. That stretch of highway became notorious for the number of head-on crashes causing death and injury. Two years into the study, it was clear that leaving headlights on during the daylight and times of limited visibility, significantly reduced the number of crashes. As far as I can recall, it was that study, by the late 1980s, that led the manufacturers of all vehicles sold in Canada to have DLRs (Daylight Running Lights) installed. It was a simple fix and it worked.

Canada Highway between Abbotsford and Hope were requested to leave their vehicle headlights on during daylight hours. That stretch of highway became notorious for the number of head-on crashes causing death and injury. Two years into the study, it was clear that leaving headlights on during the daylight and times of limited visibility, significantly reduced the number of crashes. As far as I can recall, it was that study, by the late 1980s, that led the manufacturers of all vehicles sold in Canada to have DLRs (Daylight Running Lights) installed. It was a simple fix and it worked.

In the same vein of adopting new technologies, there are hundreds of studies from around the world which reveal photo radar and red light cameras can reduce crashes in high incident areas.

D. The BC Experience

Mobile photo radar was introduced into BC in 1996, during the first term of the NDP Government. Subsequent studies revealed the units were effective in reducing crashes due to speed. I have a copy of the primary study in .pdf form but cannot find a web link. The system was bought and paid for by ICBC and managed by local police department integrated units similar to today’s IRSU.

While it was initially intended to be used on a targeted basis, management of the system was still based on the old model of general deterrence rather than focussing on high crash locations and stretches of highway. As a consequence of high volume ticketing at random locations, public opposition grew as it appeared photo radar was just another cash grab which, in many instances. it was.

During the 2001 election, the Liberals, sensing an opportunity to knock off ten years of NDP government, made dumping the system part of their election campaign. When they won, the entire system was sold to Alberta at ten cents on the dollar. So ended a system that appeared to hold the potential to actually change driver behavior in high crash areas if it had been used as intended.

potential to actually change driver behavior in high crash areas if it had been used as intended.

Note: A July 28, 2019 news report by the CBC indicates the current NDP government is rolling out speed enforcement cameras at “strategically placed high-risk intersections best suited to ticketing speeding drivers.” I have yet to put my fingers on studies that show this automated system holds the potential to actually reduce crashes at these locations (2). The new system relies upon pole-mounted cameras and remote monitoring so there is no need for police involvement as is the case with the majority of remote vehicle-mounted monitoring today.

E. The Alberta Experience

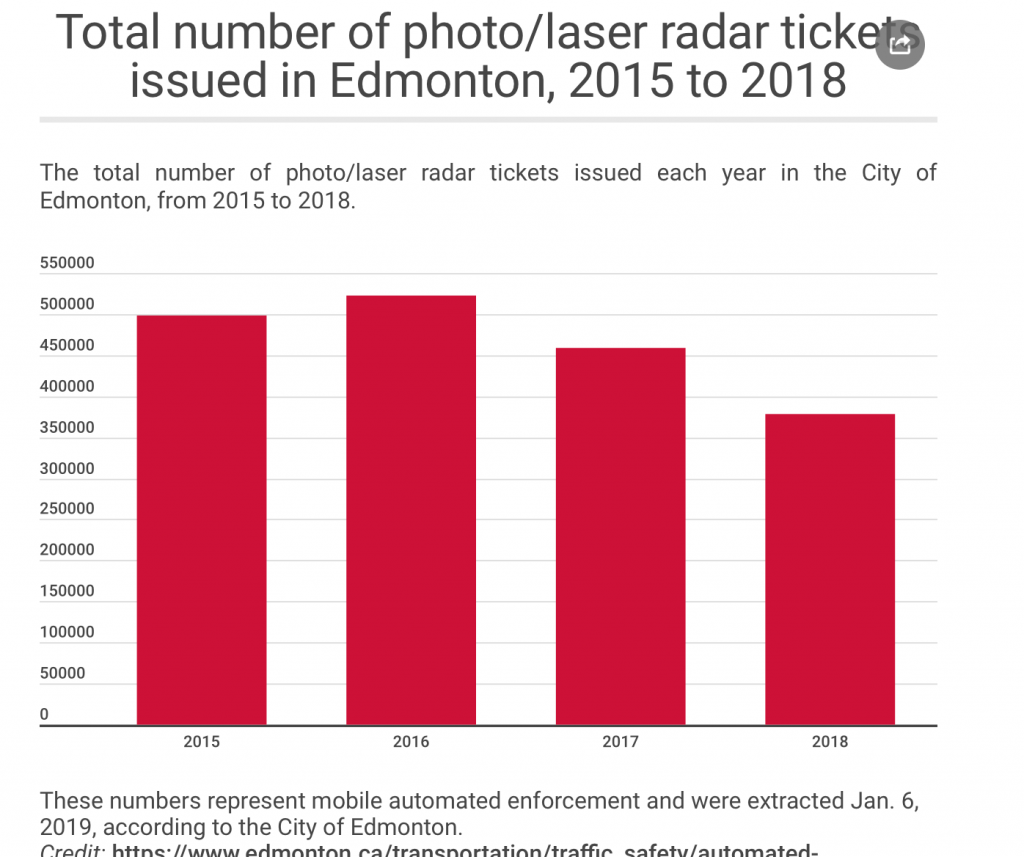

Photo radar has been in common use across Alberta since having left BC in 2001. As in BC, it appears that over time the units became more of a source of income than as the crash prevention aids originally intended. Neither does it appear any follow-up studies were conducted other than counting tickets and cash. There are dozens of news stories about the system use in Alberta, but follow-up studies regarding whether crashes were reduced are in short supply. Following bar chart of lists the number of tickets issued in the City of Edmonton:

There are nearly 1,000,000 people in Edmonton. Do the math? Remember, a lot of those folks aren’t old enough to have a drivers license (3)

As a result of the growing number of complaints from across the Province, the following guidelines were put in place early this year. Photo Radar in Alberta.

The guidelines are listed in full, as this type of restriction must be placed on all traffic sections and particularly on Integrated Traffic Units in order to bring a high degree of focus on how the units are used to actually reduce crash rates:

The Government of Alberta will work with police services and municipalities to implement several changes over the next year, including:

- Banning photo radar use in transition zones: Photo radar will not be allowed in the area immediately adjacent to a speed limit sign, where the speed limits change from a higher speed to a slower speed or vice versa.

- Banning photo radar use on high-speed multi-lane corridors: Photo radar will not be allowed on a high-speed multi-lane highway unless there is a documented traffic safety issue.

- Public awareness and transparency: Municipalities are required to post all upcoming photo radar locations and update the information monthly

- Definitions: Clarifying terms and directions in the guidelines

- Organizational roles and responsibilities: better-defined roles and responsibilities for municipalities and police services.

- Data collection: Improved collection and reporting of available data.

We will continue to work with municipalities to look at implementing future changes, including:

- Restrictions to clarify operations and to further enhance traffic safety outcomes.

- Site selection using data to better focus on traffic safety.

- Enhanced data collection to justify operations and evaluation consistently.

- Enhanced traffic safety plans to directly link photo radar to traffic safety outcomes.

It will be interesting to see if Alberta begins to circulate the results of studies which indicate the degree to which the system actually changes driving behavior and that it reduces the number of accidents involving death and injury. The following links are provided for further reading:

F. Prevention of Traffic Crashes and Deaths (literature)

The use of photo radar as a means to reduce traffic fatalities, a collection links to the literature from around the world.

Photo radar and Red Light Camera use in the City of Edmonton

Photo Radar in BC. A full assessment of the program

The following links are copied from the BC Injury Research Website.

If you have the time to link to some of the following summaries you will see why good research is necessary, and, you might also note that in some area’s the current research is inconclusive. I’m not sure if this is because the links were cherry-picked to provide sought after answers.

- Alcohol and drug screening of occupational drivers for preventing injury

- Alcohol ignition interlock programs for reducing drink driving recidivism

- Area-wide traffic calming for preventing traffic-related injuries

- Graduated driver licensing for reducing motor vehicle crashes among young drivers

- Increased police patrols for preventing alcohol-impaired driving

- Organizational travel plans for improving health

- Post-license driver education for the prevention of road traffic crashes

- Red-light cameras for the prevention of road traffic crashes

- School-based driver education for the prevention of traffic crashes

- Speed cameras for the prevention of road traffic injuries and deaths

- Street lighting for preventing road traffic injuries

6. Conclusions and Future Parts

I am still mulling over how to tackle the next Part (IV), and other parts that might be warranted in the future. It seems clear to many, the specifics of implementing change will involve some form of ‘integration’ as opposed to ‘amalgamation’.

All police departments have moved in that direction with the smallest departments Oak Bay and Central Saanich PDs, taking full part as both now have several police officers in joint force units.

No department within the CRD, and that includes the RCMP, can sit as an Island upon which everything else must be built. As pointed out in these articles, there are many ways in which VicPD can be assisted to meet the challenges they face, without resorting to full-out amalgamation.

Following is a small bit of information from one such integrated unit:

Integrated Major Crime Unit (VIIMCU)

The VIIMCU is comprised of

- Saanich Police Department

- RCMP

- Victoria Police Department

- Central Saanich Police Department

- Oak Bay Police Department

and is established to serve Vancouver Island and the Greater Victoria area as an integrated major crime unit.

The unit’s mandate includes homicides, missing persons where foul play is suspected, and unsolved homicides. The creation of VIIMCU is intended to gain the benefits of integration, where an effective case management system will enhance communication and cooperation between the agencies in order to optimize and ensure the success of major crime investigations.

On this subject, the Times Colonist carried an article this morning (August 3, 2019), How a cocaine smuggling mission ended in two slayings, and how the now two-year-old ‘drug murders’ in Ucluelet, are being investigated.

It strikes me that integrated units such as this can be a valuable asset that goes well beyond ‘amalgamation’ in many specialized investigative areas while leaving intact police organizations that can still remain close to the people they are assigned to serve and protect. Once an organization grows to cover multi-jurisdictions, any hope of maintaining local contact is lost as appears to now be the case in Esquimalt. It only costs them more for less in terms of service (I).

Of course, getting rid of traffic enforcement in its present form should be at the top of the list as that can clear dozens of members for service in area’s that actually require a highly trained and experienced police officer. ICBC and the Province, with the initial cooperation of the police, can certainly find the ways and means of structuring the entire enterprise in a different manner.

In that regard, technology is clearly the way to the future in reducing death and injury due to highway crashes. A specialized civilian-based organization will more be attuned to use of that technology and, as well, the entire organization can be run from centralized offices rather than the street. I know it sounds ‘big brotherish,’ but what is the alternative? Continuing to spend millions on an ineffective mission?

Other areas in need of immediate attention, include the ‘medicalization’ of police, a problem very similar to ‘militarization’ in its effect other than ‘militarization’ has no useful purpose.

Increasingly greater percentages of police time are now consumed with mental health issues that devolve to the street. As with drug overdoses and related issues of homelessness, this often leads to street crime and a host of other social issues that cannot be solved by the police. All the police can do is seek to restrain and contain in the most humane manner possible. When they fail, they often face severe criticism and that creates even more downsides.

It’s to easy to understand why core area police agencies, such as Victoria, can become overwhelmed and to understand why they push to hire more and more police officers. If that model of containment is to be continued, the only path to the future is more police officers. Yet, it is a downward spiral that leads to a higher incidence of staff shortages due to stress-related and other longterm challenges like PTSD.

These topics need to be given greater attention if we are to move forward in a positive manner rather than thinking all will be solved in one fell swoop with the amalgamation of police forces.

D/Sgt. Harold McNeill (Ret.)

Oak Bay Police (1964 – 1994)

NOTE: Part IV of this series is delayed for a couple of weeks due to family commitments.

Part I, Police solidarity and the push for amalgamation.

Part II, Comparing differing police cultures

Footnotes

(1) Police Department Budget Comparisons (Budget/Sworn members)

The amalgamation of police forces within the CRD continues as a central theme supported by the VicPD joint force and Mayors of Victoria and Esquimalt. A report released by VicPD on July 19, 2019, suggests financial and staffing shortages have led to a crisis situation within the department. How do the budget and staffing numbers in Victoria/Esquimalt compare to other police agencies across Canada? Would amalgamation of police forces with the CRD be more effective and cost-efficient?

Let’s simplify the numbers across Canada to see if that’s really the case and for the purpose of comparison, we’ll use Metro Toronto as that is the largest amalgamated city force in Canada. Metro Toronto was merged into one some two decades back along with dozens of other police forces across Ontario.

While the RCMP is actually the largest amalgamation overall, it’s next to impossible to calculate the sworn officer costs of the RCMP as they mix and match so many agencies and the funding sources, it’s nearly impossible to come up with a credible figure. One thing that seems certain, the RCMP is likely the most expensive force in Canada if all aspects of their costs were measured against the number of sworn members. (c)

Following are the comparative numbers for non-RCMP police agencies (budget/sworn members):

Note: The budget and sworn numbers are difficult to dig out as they seldom appear on the same page (e.g. Wikipedia). Sometimes older figures (2014, 2015, etc.) are used as those numbers will provide an accurate reading of the sworn officer cost as the overall budget and staffing numbers tend to rise proportionately.

Cross Canada 14.7 Billion for 69,027 sworn officers = $213,000. (2017)

Appendix A. Police staffing numbers and cost across Canada

The Transformation Report suggests financial and staffing shortages have led to a crisis situation within the force. How do their budget and staffing numbers compare to other police agencies across Canada? Would amalgamation of police forces with the CRD be more effective and cost-efficient?

Let’s simplify the numbers to see if that’s really the case and for purposes of comparison, we’ll use Toronto as the base as being the largest amalgamated city force in Canada. Toronto was merged two decades back along with dozens of other police forces across Ontario so there are plenty of examples.

Note: In many cases, the budget and sworn numbers were difficult to dig out as they seldom appear on the same page (e.g. Wikipedia/City budget documents, etc.). Sometimes older figures were used (2o14, 2015, etc.) as those numbers provided an accurate reading of the sworn officer costs because overall police budgets and sworn officer staffing numbers tend to rise proportionately. If you note a significant error is some number, please let me know.

Across Canada $14.7 billion for 69,027 sworn officers = $213,000. (2017) (a)

Ontario and Quebec

Toronto $1.15 billion for 5235 sworn officers = $219,000/officer. (2015) (Pop: 2,930,000)

Ontario Provincial (OPP) $1.16 billion for 5618 = $200,000 (2015) (f)

Ottawa-Carleton Regional $330 million for 1387 = $237,000 (2018) (Pop. 998,000)

Quebec Provincial (QPP) $1.1 billion for 5269 sworn officers = $209,000

Montreal Police Service I could not find reliable numbers.

York Regional Police $334 million for 1565 = $213,000 (Pop: 1.1 million)

Waterloo Regional Police $171,000 for 800 = $213,000 (Pop: 531,100)

Hamilton Police Service $178 million for 848 = $209,000 (Pop. 580,000)

Peel Regional Police $423 million for 2040 = $207.000 (Pop: 1,382,000)

Chatham-Kent $33 million for 165 = $200,000 (Pop. 105,500)

London Police Service $108.5 million for 605 = $179,000 (Pop 404,600) (this seemed a little low, so subject to further checks)

Thunder Bay PD $42 million for 246 = $166,000 (b) (These numbers seem correct, but are very low… an email sent to the department) (Pop. 110,000)

Prairies

Regina $92 million for 401 = $229.000 (Pop. 229,000) (confirmed by email)

Edmonton $362 million for 1,780 = $203,000 (Pop: 981,000)

Winnipeg $310 million for 1,450 = $213,000 (Pop: 749,500)

Calgary $512 million for 2500 = $204,000 (Pop: 1,336,000)

British Columbia

Nelson $3.6 million for 19 = $189,500 (Pop: 10,664)

West Vancouver $15.4 million for 79 = $195,000 (2017) (Pop: 42,400)

Vancouver $257 million for 1,330 = $193,000 (same year wiki) (Pop: 675,200)

Saanich $33 million for 181 = $194,000 (Pop. 114,000)

Delta $37 million for 185 = $200,000 (Pop. 110,800)

Central Saanich $4 million for 23 = $200,000 (3 officers funded o/s) (Pop. 16,800)

New Westminster $23 million for 110 = $209,000 (Pop. 71,000)

Port Moody $11 million for 52 = $211,000 (Pop. 33,500)

Oak Bay $5 million for 23 for = $217,000 (3 officers funded o/s) (Pop. 18,900) (number to be checked)

Victoria/Esquimalt $56.5 million for 250 = $224,000 (2019)(Total 110,000) (Victoria, $222,500)(Esquimalt, $261,000) (Victoria Pop: 92,140)(d) (Esquimalt Pop: 17,655)(e) (2019 budget)

Abbotsford Mun $50 million for 221 = $226,000 (very similar to Victoria) (Pop. higher at 150,000)

(a) Police Force Distribution: “Of the 69,027 police officers in Canada, 56%, or 38,911, were employed by stand‑alone municipal police services. These included 874 officers serving with First Nations self‑administered police services. In addition, 18% of all police officers in Canada were employed in RCMP (c) contract policing, 9% by the OPP, 8% by the SQ, 7% were employed with the RCMP‘s federal and other policing duties, and 2% were employed with the RCMP‘s Headquarters and Training Academy. The remaining 1% of police officers in Canada were members of the RNC.”

(b) With the exception of Thunder Bay, the numbers across Ontario fall within the range of the $213,000 national average. I could not find an explanation for the low numbers in Thunder Bay, but given they have faced inummerable policing challenges over the past several years, perhaps it’s because the city has significantly underfunded their department.

Thunder Bay also provides an interesting comparison to Victoria. The population (110,000) is about the same as Victoria and the staffing numbers nearly the same (246 vs 250). Yet, the budget in Thunder Bay is a $58,000 per officer less than in Victoria. I sent an email to Thunder Bay to check on the figures but as yet have not received a reply. Regina, another in which I noted an anomaly responded fairly quickly.

(c) The RCMP detachments were not included as their funding sources are so convoluted, particularly at the Federal level. Detachments, large and small, may include services to others (e.g. first nations, etc.). Across the country, it seems likely the RCMP is the most costly police force yet they provide cut-rates to communities choosing their service. The cost-saving by cities and municipalities using the RCMP is picked up by every Canadian including people living in the cities and municipalities providing their own police force. I rather expect their wages are brought in line with others, costs of the RCMP may increase significantly over the coming years.

(d) At some point, I noted figures outlining ‘costs per citizen’. Just to add a cautionary note on these figures. They can be misleading as costs are spread across the tax role. If a city, town or village has a high percentage of business, industry, tourism, etc., costs could be significantly lowered for homeowners.

(e) Don’t say “Poor Victoria”, say “Poor Esquimalt.”

A lot of news swirling around on the policing front these days with most items emanating from the City of Victoria. As usual, the city is complaining about the burdens they bear. I know the feeling as I’ve also noticed a lot more aches and pains as I get older.

Meanwhile, Esquimalt (that other side of the joint force) just tags along making similar complaints. But, what you may not realize – Esquimalt has a legitimate complaint. They pay a whole lot more for policing than does the City of Victoria? Here’s the breakdown.

Victoria’s Police budget is $50.5 million to which Esquimalt contributes a further $6 million. Given Esquimalt is tich smaller than Oak Bay and a tich larger than Central Saanich, one might expect they would have the same number of police officers as each of those two forces (23 sworn members). Do you suppose VicPD assigns that number of officers to Esquimalt for that $6 million? I highly doubt that given the current dismal state of affairs in the city (a perpetual problem it seems).

Based on Victoria’s $50.5 million budget for 227 members, that’s about $222,500 per sworn member. Esquimalt’s share of the joint force is 23 members (same as Oak Bay and Central Saanich). That means Esquimalt pays $261,000 for each member. That’s a lot of money for what’s likely far fewer than 23 members dedicated to serving Esquimalt. I wonder if Esquimalt has ever thought about that or are they just happy to “go along to get along?”

You can find the comparative figures for police departments across Canada in Appendix A of the link below. You might also observe that ‘economies of scale’ simply do not happen in with the amalgamated forces. What would happen in the CRD? Just like Esquimalt, the majority in the CRD would likely pay far more for a lot less with Victoria, and particularly their business community, calling the shots and reaping the benefits.

Now, don’t start feeling sorry for Victoria, they have plenty of advantages that don’t accrue to other areas of the CRD. They have everything for that matter, but what they don’t have, and what they dearly want, is control of the rest of the CRD. Right now, Esquimalt is just a poor second cousin being looked after by Victoria. They likely even let Esquimalt use the VicPD shoulder patch and letterhead. I bet they’d let the rest of the CRD members do the same.

It’s only speculative I know, but I wonder how many police departments in Canada the size of Victoria would jump at the chance of trading places with Victoria – one of the most beautiful, peaceful, welcoming cities in Canada. I’ve read that on a lot of tourist promotion sites.

If you wish to learn more about policing costs across Canada and why I think Chief Del Manak is on the right path with his Transformation Report, go to the following link. It’s a short read with a lot of linked information about what’s going on with other police departments in the CRD.

(f) Provincial Forces, as with many Federal parts of the RCMP, hold a somewhat different mandate than City and Municipal forces, so budget numbers for the regular policing part of the service could be skewed. I haven’t yet solved that comparison problem.

EndNote

If ‘economies of scale’ actually play a role in reducing overall police costs, one would expect the costs per sworn officer to be much lower for the QPP, OPP, GTA, Peel, York, Ottawa and other large amalgamated police forces across Canada. Such is not the case

(2) Driving the Patricia Bay Highway (#28), the casual observations of a retired police officer.

Most weeks I drive from Royal Oak to McTavish Road – perhaps 1500 one-way trips in the last four years. Traffic is generally smooth flowing but sometimes congested due to rush hour or ferry traffic.

In good weather in the 80 km/h zones, traffic moves 78 – 92 km/h, and in the 90 km/h zones, 88 – 102 km/h, depending on traffic. Experience suggests, going with the flow in the slow lane and allowing a safe following distance (the 3-1000 system), allows the trip to be made in almost exactly the same time as cars jockeying for position in the fast lane. Over the four years, I have not observed more than a couple of dozen traffic offences (other than follow to close) for which I would take the time to pull the driver over and issue a ticket. The primary dangers seem to involve the following:

- Follow to close (perhaps momentarily distracted) when traffic is coming to a stop at a traffic light.

- Driving slower than the traffic flow in either lane (e.g. going at or below the posted speed) causing others to take chances in passing.

- Lane hopping while looking for an advantage

- Not understanding how to merge on a high-speed highway

- The left-turn lanes between lights (e.g. Keating)

- Weather-related incidents (travelling to fast for the conditions may lead to some of the above).

As the main accident locations (2013-2017) appear to be at the traffic light intersections, from Beacon Avenue, in Sidney to Blanshard at Saanich Road, and vice versa, I think #1 above would be the main cause. I also suspect speeding was not a primary factor in the vast majority of accidents on that stretch of highway.

Over the years, along with other drivers, I occasionally pass by an enforcement blitz (always to do with speeding) as well an occasional police car pulling a driver over for some offence between traffic lights. That random enforcement likely changed nothing in terms of driver behaviour on the highway as accidents occur mainly at intersections. On occasion, the enforcement units caused more danger than the speeders (e.g. blocking a lane while issuing a ticket).

Further, the enforcement usually occurs during light traffic periods as it’s nearly impossible to speed in moderate or heavy traffic other than if you are near the front of the line at a red light. The best time to catch speeders would be in the northbound between the top of the hour and half-past during slack traffic periods when people are trying to catch a ferry. Of course, traffic enforcement officers, being the good fishermen they are, know all the traffic violation hot spots. Many of those hot spots were identified in the “Alberta Experience” above.

(3) Alberta photo/radar tickets are issued on a sliding scale:

- 1-15 km/hr over : $78 – $120

- 16-30 km/hr over : $140 – $239

- 31-50 km/hr over : $253 – $474

- 51+ km/hr over : $650 – $2000, plus the potential for a driver’s license suspension

In Edmonton, “the city’s data shows revenue from photo radar and intersection cameras generated almost $42 million in 2018, a drop from the $51.8 million reported in 2016 and the $51.3 million collected in 2017.” (Link CBC)

(2 – 14 – 20 – 169) CBC report: Ontario considers whether to implement photo radar: A cash grab or necessity? Ontarians sound off on Photo Radar.

(426)

Trackback from your site.

Comments (1)