Black Friday in Norway

Above: Artists depiction of Beaufighters from the Australian 455 Squadron attacking German Ships in a Norwegian Fjord.

Along with the Australians, the RCAF (Royal Canadian) Squdron 404 (pictured below), RNZAF (Royal New Zealand), Squadron 489 and RAF (English) Squadron 144,

took part in one the the largest Air Battles to ever take place in the skies over Norway. Bert Ramsden was part of battle.

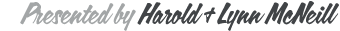

In Memory of Bert Ramsden

1921 – 2014

November 3, 2014

Pilot Officer Bert Ramsden, the subject of this story, passed away peacefully at his home in Saanich, British Columbia. The young man who fought in the Second World War shall not be forgotten.

At the age of 93, Bert joins his beloved wife, Marie who predeceased him in 2004, as well as parents, Joseph and Mercy and brothers, Cal (Eleanor) and Cec (Bess). Born in Castor, Alta., Bert is survived by his son, Don (Nancy); daughter, Karen (Chip); grandchildren, Andrea (Chris), Jennie (Trevor), Jon, Jamie and Jeff and great-grandchild, Zachary.

A memorial service will be held at 1:00 pm on Friday, November 14, 2014 at

St. Aidan’s United Church, 3703 St. Aidan’s Street in Victoria.

Below, Pilot Officer Bert Ramsden ties his shoe on the tire of his Beaufighter.

The following story was written after several interviews with Bert first at his home in Saanich and then at various coffee shops along Shelbourne Street during May and June 2014. At 91, Bert was ever the affable pilot officer who was still more than able to charm the young women at our various coffee stops along the way.

The photos in this post and in the attached photo album were copied mainly from Bert’s personal files and from various Web Sites that carried information about Black Friday. During the period of research and writing, an amazing coincidence became apparent. This coincidence was written up in a separate post that may be linked below the names of those show in the photo below.

Bert was one of the thousands of young men who left their homes, families, farms, businesses and careers to join the Second World War effort in Europe and other parts of the world. While Bert returned home without injury, many of his comrades in arms were not so lucky and it is on November 11, each year that we celebrate these young men and the sacrifice they made to make our world a better place. While I say that Bert returned without injury, it is clear he still carried with him, even at the age of 91, a degree of guilt that he walked away when so many of his flying comrades died in the battles in the skies above Norway and elsewhere.

We shall remember Bert.

Harold McNeill

November 9, 2014

Victoria, B.C.

Pilot Officer Bert Ramsden and the Flying 404

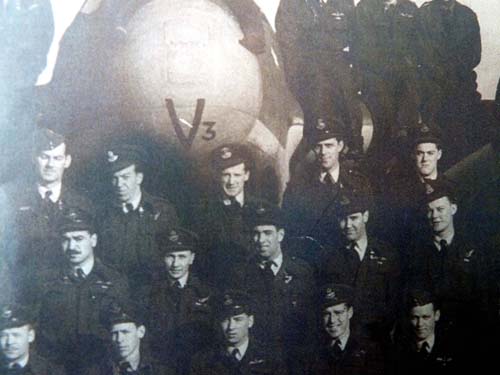

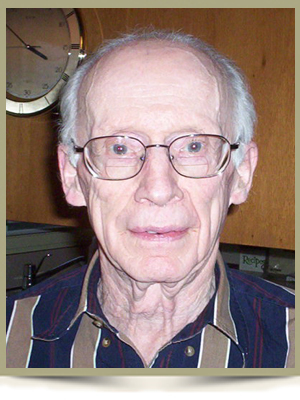

RCAF Squadron 404 (Circa Spring, 1945, Banff, Scotland)

Ramsden Photo Files: RCAF 404 Squadron, Bert Ramsden is standing

immediately below and to the right of the “V3“.

A high-resolution copy of this photo, in which all the faces and printing is clear, can be obtained by leaving a note on this posting or by sending an email to harold@mcneillifestories.com

(double click to open in a larger size)

Top Row on Wings

F/L Stewart (standing), F/O Bondy, P/O Wade, P/O Michael (standing centre), P/O Flynn (below Michael), F/L Foord (standing), F/O Nelson (front of Foord), F/O Gibbard, W/O Gracie, F/O Catrand.

Second Row Down (immediately below wing L/R)

F/S Aube(y), F/S Orser, F/O Mallilieu, F/O Williams, F/Lt Hill, F/O Cook, F/O Burns, P/O Bryce, P/O Ramsden, P/O Elliot, F/O Jones, F/O Bedwell, P/O Wright, P/O Camanella

Second Row Below Wing

F/S Henderson, F/Lt Ball, P/O Landry, F/O Aljoe, F/O Coyne, F/O Tomes, F/Lt Rancourt,

F/L Toon(e), F/Lt Jackson, F/O McKnight, P/O Temple, F/O Lee, F/O Johnson, F/O McCallan,

P/O Moe, F/O Stansak, F/O Miller, F/O Jasper.

Bottom Row (L to R)

F/O Panuk, not named, F/Lt Wilkinson, F/Lt Hill, Capt Chodoroff, S/Ld Inman, F/Lt Bolli, S/L Schoales,

W/C Pierce, S/L Christison, S/L Jones, F/L Watlington, F/L Beacook, F/L Spencer, F/L Corder

F/O Hines, F/O Keele

Missing from Photo

F/O Elbury, P/O Wallace, W/O Rumble (P/O Ramsden’s Navigator)

For an Amazing Coincidence regarding placements in the above photo

LINK HERE

To view the full set of photos of events surrounding this story:

Link here to McNeill Life Stories Facebook Page

A Pittance of Time (For Video Link Here)

Black Friday: An Epic Air Battle of World War II

1. The World at War: Remembering our History1

Gaining a better understanding of the sacrifices made by Bert Ramsden and hundreds of thousands of other Canadians and others around the world during the thirty year period from 1914 – 1945, is an important part of this story. It is also an important part of our own family history. Before beginning Bert’s story in Chapter 2, a little history of the world at war is in order.

Having travelled through many countries devastated by the two wars in the first half of the last century, Lynn and I could not help but gain new respect for how millions of people have rebuilt their homelands over the last 67 years. Passing by and visiting War Memorials and Museums is a stunning reminder that tens of millions of men, woman and children lost their lives.

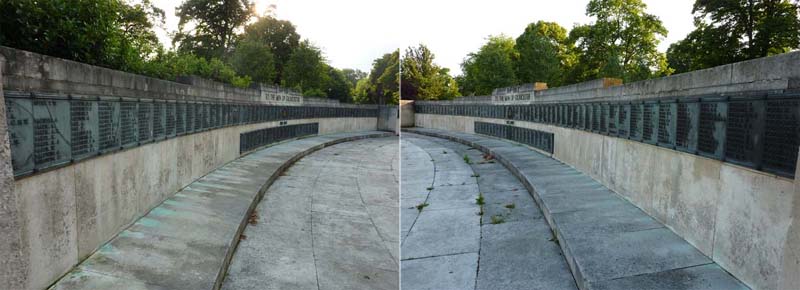

When in England, we paused at one War Memorial in Glocester (the home city of two of Lynn’s first cousins and their families) drawn by the immensity of the memorial. About six feet high, it stretches in a great semi-circle for a full block along which is displayed the names of hundreds of men from the community who lost their lives in the two world wars.

Glocester War Memorial Photoshop Merged

There are many other similar memorials spread throughout Glocestershire

Each name, with surname first, is etched on a bronze plaque in the alphabetical order. It does not take long to realize that many families in Glocester, which was largely untouched by  the German bombing raids into England, had lost multiple family members. Father’s, son’s, uncles, cousins, grandchildren and down the line as the same surname stretched for ten, sometimes twenty repeats. In England, Scotland and Wales there are 54,000 more war memorials of various types. Attempts are being made to catalogue and publish all the names appearing on those memorials.

the German bombing raids into England, had lost multiple family members. Father’s, son’s, uncles, cousins, grandchildren and down the line as the same surname stretched for ten, sometimes twenty repeats. In England, Scotland and Wales there are 54,000 more war memorials of various types. Attempts are being made to catalogue and publish all the names appearing on those memorials.

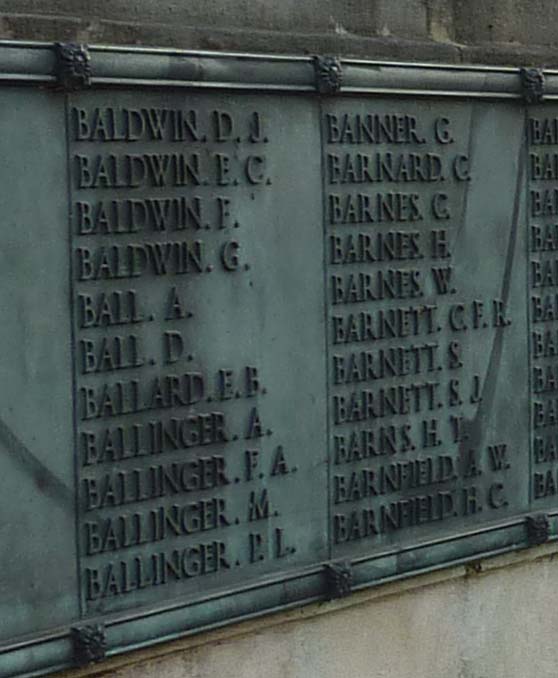

Photo: One small section of the “B” names at Glocester.

It is impossible to comprehend how those losses must have affected that single community in the tranquil English countryside. From our perspective, coming from small town’s in Alberta and Ontario, it meant that something in the order of 25% of all the men in those two communities would have died during the two wars. When adding in civilian deaths in bombed cities, the total could easily reach 50%.

This same story was repeated hundreds of times across the length and breath of Europe, Eastern Europe, Japan, China, the Philippines, North Africa and dozens of other countries around the world. The death toll is incomprehensible. Consider the following numbers.

The First World War (1913 – 1918) claimed the lives of nearly 10,000,000 soldiers and 8,000,000 civilians. The Second World War (1939 -1945)) claimed a further 23,000,000 soldiers and 40,000,000 civilians. These numbers include 6,000,000 Jewish civilians. Never, in the history of mankind, have as many people been killed in conflicts between countries.

While Canadians on the homefront were spared the death and destruction that was daily visited upon many other countries, the men and woman of the Canadian Armed Forces played an extraordinarily large role and paid an extremely high price in the two wars considering our population in 1940 was just 11 million. Canada’s official war historian, C.P. Stacey, wrote that with the exception of two small groups, all 494,8742 World War II, Europe-bound service personnel, embarked from Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Of these, 50,000 would not live to return and tens of thousands of others were seriously injured.

From the time the men and women of the military boarded a ship bound for England or some other part of the world, they well knew their chances of being killed or seriously injured was very high.

Ships such as the Cunard Liner, RMS Scythia, (pictured here in a 1938 Post Card) carried Canadian troops to and from Europe. It was on this same ship in 1956, that my wife Lynn, when four years old, travelled to Germany with her Royal Canadian Air Force father, Flight Sergant Earl Davis, and the rest of her family3 after her father was assigned to RCAF #3 Wing in Zweibrucken, Germany. During the Second World War, Lynn’s father served with the Canadian Army in the Italian campaign. While still in his teen’s he was among the first troops sent to Europe and on his return he never spoke to his wife or children about his war experience. He passed away in 1976 at the age of 52.

Much has been written about the two wars, yet, in a general sense, 67 years later, it is hard to relate to the sacrifices made. The listing of names on a memorial is an important form of remembrance, but a list does not bring to life the personal story that is hidden within each of those names. Nor does it address the hundreds of thousands who served and then returned.

Perhaps then, one story or film about one individual can serve to better to remind us of the sacrifices made by each of the many including young men such as Lynn’s father who, for reason’s known only to himself, never felt able to tell the story of his war experience. It was with these thoughts that, after having the good fortune to meet a World War II veteran, Bert Ramsden, I jumped at the chance to hear about his experience. The result, Bert’s story.

Footnotes and References

1 The Twentieth Century World: An International History by William R. Keylor, Oxford Press (2001): Among other subjects, the book provides an excellent outline of the “Thirties Years War (1914 – 1945) (p. 43 – 242)

2 This number does not include Royal Canadian Navy personnel serving on RCN war ships, nor the Merchant Marine and other civilians serving on commercial shipping vessels tasked with the job of moving men and supplies.

3 Lynn’s father met and married Lynn’s mother, Edna, while Earl was stationed in England.

World War I Death Count: Link Here

World War II Death Count: Link Here

Troop Ship Sailings: Link Here

Queen Mary: Link Here

Second Quadrant (Octagon) conference: Link Here

2. Meeting a World War II Veteran

It is not everyday that one has a chance to meet a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force who served during World War II. With 72 years having elapsed since the war began and 67 since it ended, veterans alive today are now in their late eighties and nineties with a sprinkling of spry young men and women over the 100 mark. Flying Officer (F/O), Bert Ramsden, a member of the RCAF 404 Squadron, stationed in Scotland for the last two years of the war and now his tenth decade, is one such man.

Having just turned ninety-one on June 9, 2012, Bert has seldom spoken publicly about his war experiences but did so recently when invited to a Torsken Klubban (Victoria Chapter of the Sons of Norway) dinner meeting by our boss and esteemed President, Robert A. Gunderson, a veteran pilot in his own right.

experiences but did so recently when invited to a Torsken Klubban (Victoria Chapter of the Sons of Norway) dinner meeting by our boss and esteemed President, Robert A. Gunderson, a veteran pilot in his own right.

Photo: Club President, Robert Gunderson introduces Bert to the club members. A photo of the club group with Bert is inserted in the attached files.

Now why F/O Ramsden in particular? It would be sufficient that he was a World War II veteran, but there was another very good reason – in the 32 missions F/O Ramsden flew with the 404 Squadron during the war, all were over the North Sea and nearly all into the Fjords of Western Norway. During those missions, his Squadron sank or seriously damaged almost every German ship or target of opportunity they could find.

Today, Bert is one of two surviving air crew member of the Squadron, the other, Pilot Officer Miller Bryce lives somewhere in Montana. Although there may be members of the ground crew still living, Bert and Miller both appear in the above photograph. The photo must have been taken near the final days of the war as the names of those killed in action are not listed.

The entire Squadron, pilots and navigators, as well as others from England (144 Squadron), Australia (455 Squadron) and New Zealand (489 Squadron), were hailed as heroes in Norway not only for having spent much of the war penetrating deep into enemy held territory, but also for having participated in one of the largest air battles ever waged in the skies over Norway. That battle, fought late one afternoon in early February 1945, claimed the lives of over a dozen of Bert’s friends and flying buddies in a pitched encounter over Forde Fjord, a battle that lasted less than twenty minutes. The day is  remembered as Black Friday.

remembered as Black Friday.

Photo (Bert’s Files). In this cropped section of the Squadron photo, the only two current suriving members of the air crew is P/O Bert Ramsden and P/O Miller Bryce, both standing side by side immediately below and on each side of the V3. Is that not an amazing coincidence?

As one of the surviving members of that battle and of the 404 fighter pilots and navigators, this story will focus on F/O Ramsden as a means to bring home the story of the other men (air crew and ground crew alike) who served so valiantly in World War II.

In the footer are photos were taken of items in Bert’s memorabilia collection that have followed him since returning to Canada after the war. This story and the attached photos are presented as a lasting salute to the valiant men of the 404 and of all veterans who gave selflessly of themselves in order to secure freedom for all who would follow.

For those who have sons or daughters in their teens or early twenties, pause for a moment to think what it would be like to watch your children marching off to war knowing that a large percentage of them would never, ever return home. Only memories would remain of that handsome young man or that beautiful daughter, standing proudly in their uniform.

3. The Early Years

Bert H.W. (Herbert William) Ramsden was born in Castor, Alberta on June 9, 1921, to Joseph and Mercy Ramsden. A gentle, soft-spoken, humorous man of slight build, and at just over 5’5” displaying an upbeat attitude and zest for life that belies his 91 years, it is pure joy to sit, chat and joke around with Bert.

After his wife of 59 years, Marie, passed away in 2004, Bert now lives independently in an apartment in a senior’s apartment complex in Gordon Head. An avid tennis player, as was his wife, Bert has dropped tennis but still golf’s three days a week at the Uplands Golf Club where he has been a member for 45 years. It was between his apartment and a coffee shop on Shelbourne Street that Bert related details of his early life and war experience.

In Bert’s words:

I was born in 1921, after World War I and before the depression, so I guess you could say my early life through to High School was somewhat sheltered from both World War I and the emerging conflict in Europe that lead to World War II. That my parents had moved the family to the remote mining community of Nelson, British Columbia, when I was just seven, also kept us somewhat isolated from world events and from some of the effects of the Great Depression.

In Nelson, mom and dad had built a thriving a dry goods business, J.R. Ramsden and Company, which provided the family with a comfortable living. As with kids in many small communities around Canada, life was good. Everyone knew everyone and families always helped families in the hard times.

hard times.

I attended Central School, Trafalgar and then the old L.V. Rogers High School until I graduated in 1939. During those years, while working part-time in our family store, I played hockey and was involved in track and field. As a teenager, I did the usual running around but managed, for the most part, to stay out of trouble. Actually, it was hard to do anything wrong without your parents finding out as someone in town would always see you, especially if you were acting out of line.

One thing my friends and I often talked about was getting out too see more of the world. I suppose, in a sense, the war in Europe gave us that opportunity. It was only a couple of years later, in 1942 after I had just turned 21 that I made the decision to enlist. While my parents were not overly happy, they did respect my decision. A few weeks later, after checking out the three services, I choose the Air Force as I decided to become a pilot.

While I was not worried about the written tests, I was concerned that my small body frame might exclude me from air crew. During the testing, even after a good stretch, I was barely able to push full left or right rudder, something, it seems, that was considered an essential part of becoming a fighter or bomber pilot. Next, I nearly flunked out when I failed to pass the ‘lung capacity’ test.

After a little fast talking, I managed to convince the Doctor that I recently had a cold that had left me short of breath. I asked to retake the test again the following day. I suppose the Doctor liked my attitude and determination, so agreed to see me again, but he told me that another failure would see me shunted to ground crew.

That night I stayed awake exercising my lungs by taking and holding deep breaths. Dizzy from a long night heavy breathing (note: I questioned Bert closely on this particular part of the statement), the next morning I passed the test with flying colours.”

With the last hurdle passed, I was given my joining instructions and on December 4, 1941, was off to #3 Manning Depot in Edmonton for orientation into the Canadian Armed Forces. It was all new and so very exciting.

For Bert, this would be just the beginning of an amazing experience that would stretch to the end of the war and the final few bombing and strafing missions into the Fjords of Norway. For a young man with little worldly experience, it was to be an exhilarating, yet deadly serious, time of his life.

4. RCAF: Basic Training

As with all recruits, indoctrination into the service was the first step. This was completed at #3 Manning Depot in Edmonton between December 4, 1941, and February 14, 1942. Following that, the next several months presented a whirlwind of flight training at various RCAF bases across the Canadian prairies, including:

#7 SFTS MacLeod (February 14, to March 28, 1942)

#2 ITS Regina (March 28, to August 17, 1942) (Company #50)

#15 EFTS Regina (August 17, to October 10, 1942) Company #52)

#15 SFTS Claresholm (October 10, 1942 to March 5, 1943) (Company #66 and #68)

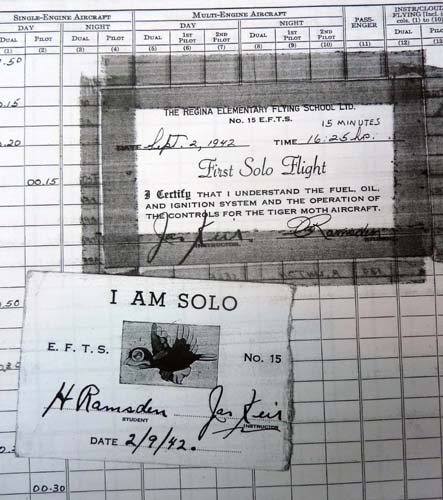

During this time Bert did his initial training on a Tiger Moth following a pattern of training that remains much the same as it is today (see sample log book entries). Following the initial training, he completed his first solo on September 2, 1942, while in Regina.

During this time Bert did his initial training on a Tiger Moth following a pattern of training that remains much the same as it is today (see sample log book entries). Following the initial training, he completed his first solo on September 2, 1942, while in Regina.

Web Photo: In 1937, the RCAF ordered 25 DH-82As (Tiger Moth) from de Havilland Canada, a milestone as it was the first time a de Havilland design had been so extensively modified in Canada. Modifications included float and ski fittings, sliding canopy, cockpit heater, redesigned cowling, increased power, and a tailwheel. Soon after this, Britain odered 200 Tiger Moth fuselages which were a reversal of the usual flow of Aircraft between Canada and Britain. Above, number 4197, was one of 1384 DH-82Cs that served with the RCAF from 1940 to 1946, in addition to the 26 DH-82As that served from 1938 to 1948. (Link information from Web)

NOTE: This very series of the Tiger Moth, including #4197, were used as trainers by Bert and his flying mates. Reference his log book entries for the summer of 1942 posted on FACEBOOK (Link Here). In the first entry for August 8, Bert was flying #4192.

Bert well remembers that first solo as well as his many instructors. The fact they were training in an aircraft capable of acrobatic flight, was an added bonus. At one point during later training months, one instructor taught him how to follow a freight train along the prairie flatland ‘while inverted’. Bert loved the exercise and became very proficient in every form of ‘unusual attitude’ something that might be expected of a pilot when in the heat of battle. On this count, he would get plenty of live practice.

something that might be expected of a pilot when in the heat of battle. On this count, he would get plenty of live practice.

Bert’s Files: Notation in his Pilot’s Log Book of his first solo at 16:25 hrs., September 2, 1942.

As the saying goes, it was not ‘all work and no play’ over those long months of ground school and flight training. Bert and his comrades, mostly single and many in their late teens and early 20’s, managed to charm the local girls with their flashy uniforms and tales of daring over the prairie skies. This, of course, did not sit well with the local males, who could only watch as those daring young men beguiled “their” women. More than once there was an attempt to even scores with fisticuffs.

For Bert, Regina was to be a fortuitous posting as it was there he dated a young woman, Marie Jamieson, who, immediately following the war, would become his life long partner and the mother of their two children, Don and Karen.

As an interesting note, many of the military recruits could not enter a drinking establishment as the drinking age was 21 for the men and, in Saskatchewan at least, women of all ages were outright banned from entering a drinking establishment. It now seems illogical that women were treated in this manner, but it is equally illogical that these same young men and woman were deemed old enough in their late teens and early twenties to fight and perhaps die for their country, yet could not legally enter a drinking establishment or possess liquor. For the women in Saskatchewan, it was not until the early 1960s, that they finally gained the right to enter.

5. Off to War with the Prime Minister of England

As Bert progressed through his flight training he was then assigned to #1 GRS Summerside (March 13 to May 21, 1943 (Company #82), and #36 OUT Greenwood (May 29, August 13, 1942) (Company #29 and #3), where he completed his twin engine and limited IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) training. After two weeks leave, Bert was sent to Halifax in late August in preparation for transport to England and active duty.

Unbeknown to Bert and his troopmates, highly secret meetings were being held in Canada between Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King and President Franklin Roosvelt. Codenamed “Octagon”, the first conference was held in Quebec City in mid-late August 1943. Among other discussions, the three leaders began the process of deciding how to divide up Europe after the war. Depending on how the war progressed, further meetings would be scheduled for the following year.

in mid-late August 1943. Among other discussions, the three leaders began the process of deciding how to divide up Europe after the war. Depending on how the war progressed, further meetings would be scheduled for the following year.

Photo (Web): Formal dinner held at the Hotel Frontenac in Quebec City during the Octagon conference.. (L-R): Mrs Clementine Churchill, Sir Eugene Fiset, Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt, Rt. Hon. W.L. Mackenzie King, Lady Fiset, Hon. Ray Atherton

After the conference concluded, Churchill was secretly whisked back to Halifax to again board the Queen Mary. That return trip was also scheduled to carry a compliment of 15,600 Canadian troops1 and something in the order of 900 crew. Bert, completely unaware of the Prime Minister being one bard, was among those Canadians. Bert continues the story:

“It seemed like chaos as thousands of troops began arriving at Pier 21 to begin the process of boarding the Queen. Standing on the jetty and seeing that huge ship towing above us was something I could never have imagined. Neither I, nor any of my troopmates, all of whom were with me, had ever been on a ship let alone one of this size and one that would be sailing across the Atlantic to England. We just didn’t see ships like that in Kooteney Lake.

All we carried on board was our basic kit and after being assigned sleeping quarters (how many to a room?) we settled in for the four or five-day trip. Initially, we were all bedding down in the theatre in beds standing in tiers about eight or ten high.

All we carried on board was our basic kit and after being assigned sleeping quarters (how many to a room?) we settled in for the four or five-day trip. Initially, we were all bedding down in the theatre in beds standing in tiers about eight or ten high.

We knew the trip would take longer than usual to take longer than usual as the Queen, running without escort ships as it was so fast, ran a random zigzag course so the German submarines could not zero in on her route.

I think our ship was loaded heavier than usual because a troop ship that had left a few days before ours, had been sunk by a German submarine. Hundreds of the men who were rescued were brought back to Halifax and boarded the Queen. As some of those men had been through a harrowing experience, they received to be a priority so I was ordered to take my blankets and gear and move to the upper deck next to one of the Oerlikon guns which I was taught how to fire. It was here, under the stars, that I spent the rest of the trip.”

With the rescued military personnel on board, Bert estimated the passenger load on the Queen must have neared 20,000. All this time no one realized the Prime Minister of England was on board. It must have been a difficult decision to stop the Queen as that would have left the ship extremely vulnerable to enemy attack. For the Germans to sink the Queen Mary with the Prime Minister of England on aboard, would have been a major blow to England and to the allies. As it turned, the ship made the stop and then continued to England without further incident.

In mid-September Bert then reported for duty at the Royal Air Force (RAF) Station at Bournemouth, England where he was assigned to the #3 PRC for further training. After the posting to RAF Bournemouth, then bases at Ossington and Burtonwood, where training continued, he was finally assigned to Damhead. By this time Bert was qualified on the following twin engine aircraft: Cessna Crane, Avro Anson, Hudson Mark III, Wellington, Beaufort II, Oxford and Beaufighter.

The first two, Cessna and Anson, were training aircraft, the others, multi-purpose light bombers and fighter bombers. He needed only to make his first few missions into enemy territory to begin the process of becoming a veteran combat pilot, all by the tender age of 22.

multi-purpose light bombers and fighter bombers. He needed only to make his first few missions into enemy territory to begin the process of becoming a veteran combat pilot, all by the tender age of 22.

Of the aircraft types on which he qualified, by far and away his favourite was the Beaufighter (picture here over Scotland near Wick airfield). It was powerful, with twin Bristol Hercules XVII, fourteen-cylinder engines that were each rated at 1,725 hp at 2900 rpm for takeoff and 1,395 hp at 2400 rpm at 1,500 feet. It was also known to have a strong fuselage and wings that could withstand a tremendous amount of bullet and flak damage and still keep flying.

It was, in short, a fighter-bomber to be reckoned with as it was extremely responsive to the controls even when heavily armed with four 20 mm Hispano cannons in the nose, six .303 in. machine guns in the wings, one .303 in. Vickers “K” or Browning in the dorsal (navigator) position and externally, one 18 in. torpedo under the fuselage.

Depending on the particular mission, eight wings mounted rockets could be carried as an alternative to the wing mounted guns. The Beaufighter, once having dropped its torpedo or having fired its rockets could, when fitted with the wing mounted machine guns, quickly transition to a fighter role with sufficient firepower that could prove deadly to the enemy.

From Damhead, in a Beaufighter, between January 19th and April 6th, 1944, with the 404th Squadron, Bert was initiated into the deadly world of seeking and destroy within the Fjords of the flak filled Norwegian coast. While the dangers hidden within the flak filled Fjords could not be minimized, neither could the 400 to 600-mile return trip across that dangerous stretch of water known as the North Sea.

In order to remain undetected by German radar, the bombers never flew above 50 feet and often skimmed the waves at 20 feet. With a brisk wind blowing in low visibility it seemed the whitecaps were forever kicking up salt spray onto the windscreen and on more than one occasion the tips of the propellers nicked the top of a wave. With an endless stretch of rolling water that spread to the horizon, it was very easy to become mesmerized. Throw in some low cloud with a light rain or skiffs of snow and it would be easy to become disoriented. Loss or orientation or a momentary lack of focus at such a low altitude could lead to a disastrous result.

Painting (from Web) This is a particularly good scene of two Beaufighters just off the Burmese Coastline. The conditions would be very much like those experienced by 404 and other squadrons as they made their way to and from Norway. The heavy clouds in the background indicate just how difficult the job of piloting and navigating would be without the many avionics available today. Link Here

During the runs toward the targets, a senior pilot and navigator would lead the bombing raid in a “V” formation of three and, occasionally five, aircraft. The job of the trailing pilots was simply to keep track of their wingman (on either the left or the right). If suddenly the leader was to take a dip in the drink, it was very likely that one or more of the trailing aircraft would arrive at the same spot. After several successful missions from Ireland, Bert and his comrades became confident and were soon on the move to Scotland, where they flew from the RAF Base at East Fortune from April 7 to October 10, 1944.

It was from the base at East Fortune, that Bert became more proficient at directing his torpedo and/or rockets on target. It was an experience he found hard to describe. When asked if he was afraid when moving across the North Sea or into attack mode, Bert explained: There was very little time for fear as such a high order of concentration was needed to complete the flight and the attack, that fear seldom had time to enter your mind.”

Bert explained further:

When you were in a fjord (on a search and destroy run), it was much more difficult than if the ships were out in the open sea. This was because we always attacked in a “V” formation in order to concentrate our fire power and to overcome the defences. With several planes closing in on a ship at the same time in a narrow Fjord, it often appeared as if we were going to hit one of the other aircraft. It was a touchy situation; because the targets would tuck themselves in close to a shoreline and, after the attack, there were always those bloody cliffs. There was no time to second guess as you barely had sufficient time to bank hard and make your pull-out.

With a heavy blanket of flak flying around, there was little to think beyond completing the attack and getting out. Our pilots and the squadron as a whole were very effective on most runs as one hit from a single torpedo or a few hits from the rockets, would be sufficient to inflict considerable damage.

The following picture, from Bert’s file (details are written on the reverse of the photo), was taken as Beaufighters information bear down on a German ship. This particular ship was in the open water so was a much easier target than when hidden within a Fjord.

Even returning from the battle was no picnic. Bert explained:

Aircraft were sometimes damaged, the weather could change for the worse or problems with engines and damaged controls could make the return to stretch to an eternity. More than once we came back with holes in our wings or elevators.

As we often left the battle field at different times, we seldom flew in formation on the way back, so the pilots and navigators had to make their own way. A few planes usually tried to stay together in the event someone had to ditch, but occasionally we ended up on our own. A real worry with a damaged aircraft was ending up in the salt chuck. With the water temperatures hovering just above freezing, the crew of a ditched craft, if left in the water, would not last more than a few minutes. Of course, with no alternative, everyone did their utmost to nurse a sick aircraft back to dry land.

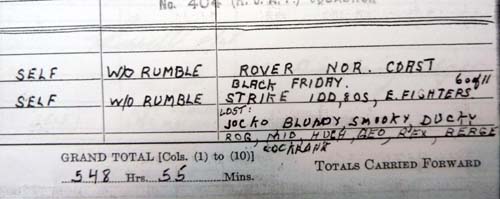

Bert remembered on one return trip when his navigator, Warrant Officer Roy Rumble, made a small miscalculation in his dead reckoning route, they ended up about 20 miles south of the airfield. The mistake was not large and the error was easily corrected when over land, but Bert always teased Roy about not being able to find his way home.

I then asked Bert about his remembrance of the Black Friday battle. It was not something he often talked about but both at the Sons of Norway Meeting and again when we had coffee, he spoke with reverence of the bravery of his squadron members. The memories and the feelings they evoked were as fresh today as they were nearly seventy years earlier.

Footnotes

(1) The records of the ship manifest and troop movements between North America to England and other points has only partially been patched together by veterans and other researchers. This was the result of a 1951 order by the US Government that all troop ship manifests were to be destroyed. I was not able to determine why that order was given, but it was likely due to the emerging Cold War and a fear those records could somehow be used by Russia for some nefarious purpose.

6. Black Friday

With the 404 finally settled in Scotland at RAF Banff for the last eight months of the war (October 11, 1944, to June 21, 1945), Bert served as a Pilot in Command on the Hudson, Wellington, Beaufort II, Oxford, Beaufighter, and Mosquito bombers, but primarily flew the Beaufighter. Other squadrons flew out of nearby RAF Dallachy.

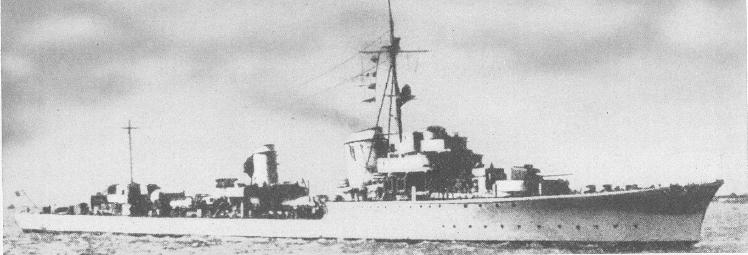

It was from RAF Station Banff, on the afternoon of Friday, February 9, 1945, that Bert and his comrades from the 404 and air crew from three other countries (Australia, New Zealand and England) would fly to intercept the German Narvik class Battleship Z-33 (photo below).

Norwegian intelligence had learned the ship may have been damaged during a recent grounding and was limping to Trondheim for repairs. As the small convoy accompanying Z-33 travelled mainly at night to avoid the attack, they holed up each day in the Fjords along the route. It was believed they were currently anchored in a well-protected area of Forde Fjord near the remote community of Naustdal. Maps of the battle location are provided in the footer.

The intelligence was solid, so two ‘outriders’ from 489 Squadron were assigned to fly an advance reconnaissance mission into the Fjord. Shortly after, a “confirmed” sighting message was received. The possibility of catching the damaged Z-33 was just too good to pass up so a large squadron of Canadian, British, Australian and New Zealand fighter-bombers and cover fighters, all under the command of an experienced Australian Air Force Wing Commander, Colin Milson, was prepared. The combined squadron of 45 planes departed just before 14:00 hours.

From this point, I have summarized the story as told by F/O Ramsden with additional details taken from a written report by various authors including F/S Stan Butler of 144 Squadron appearing in an article titled: Luftwaffe Sig Home Page (Link Here for an excellent minute by minute description of the battle).

Bert recalled:

We had been ‘standing down’ through much of January as the weather across the North Sea had been dreadful. While we often flew in bad weather, that January even the ducks were grounded. During these times we just hung around the barracks, played cards, wrote letters home and otherwise kept ourselves occupied. I was certainly glad I had joined the Air Force and felt sorry for the ground troops who had to suffer things out in temporary quarters on some remote battle field.

On the occasional mission, we observed ground troops bivouacked on a muddy field and we all thought how much better it was to be able to fly back to your base after your mission to find a hot meal and a warm bed. Although this somehow seemed unfair, it was just my good luck I had chosen the Air Force and in war, it seemed the luck always played a big role.

We heard scuttle that a German battleship had been observed along the coast and that a couple of Beaufighters had been sent out on a reconnaissance mission. Even before confirmation was received, preparations were being made for a raid that, we had heard, would involve fighter-bombers from several squadrons.

The raid was to be lead by an Aussie Wing Commander, Colin Milson. Although I did not know the Commander, I had heard he was a very experienced leader but didn’t have much experience in conducting an attack within the narrow confines of a Fjord. These attacks, as I had learned from many raids, required special knowledge of how to properly approach the target.

The procedure we usually followed was to fly at a low level to the Norwegian coast line, then climb just high enough to clear the coastal mountains and head toward the selected target area. We would then commence the attack in a V formation in a direction, usually East to West (toward the coast), as this allowed us to break off after the attack and exit directly out of the Fjord. By doing this we expected the element of surprise would allow a clean get-a-way to the open sea before enemy fighters could be alerted and arrive on the scene.

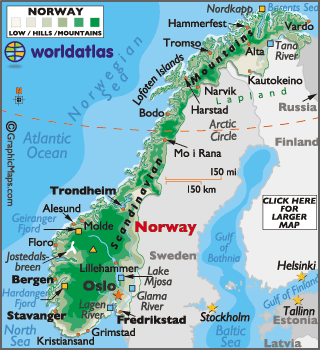

Forde Fjord ran Westward from a point just south of Floro

(midway between Bergen and Trondhelm

Additional Maps in the footer.

F/S Butler, in his notes, reported the planes took off from Banff in overcast, but generally good weather, just before 14:00 hrs. The group arrived along the Norwegian coastline near Sognefjord at about 15:40 and two ‘outriders’ were sent ahead to scout the target. They returned a short time later without having made contact but it was assumed the targets were still anchored in Forde Fjord. The attack group formed up, changed course and arrived at the East end of the Fjord just before 16:00. The plan was to attack from the landward side, drop down over the Naustdal, complete the attack and exit out the Fjord.

As they cleared the high ground, heading in a westerly direction, the group expected to see the target ships further down the Fjord, but, as it turned out, the ships had anchored near the north-east shore and the bombers were too high to make the attack.

As they passed over the German ships their planes had to fly through a heavy blanket of flak laid down by Z-33 and her escort vessels. It was clear the Germans had been expecting them and had anchored themselves in the most advantageous position.

The following notes are taken from the 404 Squadron Home Page (Link at 404)

In the fjord, two vessels situated themselves against the sheer cliffs, the Z.33 was on the opposite side of the fjord and three flak ships were in the centre with excellent arcs of protective fire. To top it off, there were several batteries of anti-aircraft guns situated around the shoreline. Normally, the Wings attacked using surprise, catching an unprepared enemy, quickly striking then escaping. It seems obvious that in Førde Fjord, this was not the case – the enemy was prepared, well sited defensively and fairly close to protective fighter-aircraft bases. As was to be seen, the Strike Wing was flying into a nightmare scenario.

In fact, the vessels were so prepared that some of the vessels had non-essential personnel evacuate before the attack, and some civilians were even instructed to seek safe haven in their cellars. Unfortunately, the extra time taken to set up the attack allowed enemy fighters to get airborne from the airbase at Herdla. The nimble fighters included some of the latest marks of FW.190s and many of the pilots were battle-hardened veterans of the Russian front, including ‘Blue 4’, flown by Lieutenant Rudolf Linz, an ace with 70 victories.

When the targets were found, the Strike Wing was not prepared to attack “and the formation leader orbited the force twice to get into a suitable attack position to attack and then ordered the attack up fjord. As the Beaufighters made their way in, they met an intense crossfire in the form of a box barrage ”.

With the coveted destroyer well protected, the attack runs were made, but the tightness of the fjord and the danger of aircraft colliding forced the Beaus to fly through anti-aircraft fire. Flying into a swirling hell of flak, the Beaufighters made their attacks. Some reports indicate that the three flak vessels in the middle of the fjord received the brunt of the attacks, but Z.33 was also targeted, with many near misses.

Short of aborting the mission and taking a secondary target (a group of German supply vessels known to be further out along the coast), the decision was made to climb out, regroup and conduct the attack in the opposite direction (west to east). This created the additional problem of diving in to attack and then climbing out sharply and climbing high to avoid the high ground to the east. This was far from an ideal situation.

Short of aborting the mission and taking a secondary target (a group of German supply vessels known to be further out along the coast), the decision was made to climb out, regroup and conduct the attack in the opposite direction (west to east). This created the additional problem of diving in to attack and then climbing out sharply and climbing high to avoid the high ground to the east. This was far from an ideal situation.

Photo from Web: Taken from Beaufighter firing rockets at the Z-33 in Forde Fjord.

Bert continued:

After forming up, Commander Milson and his formation began the attack. I was assigned to one of the following formations and due to the narrow attack area, we had to wait in a holding pattern for our turn. It was during the first attack that someone reported a small formation of planes coming in from the south. Below, we could also see the German gunners must have been very experienced as they laid down a very effective blanket of flak along our approach run toward the Z-33.

Photo from Web: Rockets strike near the bow of Z-33.

A few minutes later our group commenced our run, but the radio chatter made it clear that at least one squadron of Luftwaffe fighters had arrived and was attacking the waiting bombers. This was very bad news as we were now more or less trapped at a low level in a very narrow Fjord with heavy flak coming up from below and German fighters from above. We knew our waiting bombers would be vulnerable. As usual, following our run, we were ordered to break off and head for home. Also, as our wing guns had been replaced with rockets, we had no means of effectively fighting the Luftwaffe.

Meanwhile, the escort Mustangs and Spitfires were engaged in a pitched battle with the German Focke-Wulf fighters. The fight spread across the top of the Fjord during which time the waiting Beaufighters suffered severe losses. The entire battle was over by 16:30 (less than 15 minutes after it had started) when the combatants broke off and headed back to base. Within the allied ranks several planes had been shot down and of those still flying, several were seriously damaged.

The following notes appear in the Luftwaffe Home Page:

The remaining Beaufighters, Mustangs, and Spitfires, many of which were damaged, flew singly or in small groups all the way to Dallachy. Not only the planes had suffered; but aboard the Beaufighter UB-X of 455, F/O Spink, the pilot, was severely wounded. The navigator, F/O Clifford, had suffered a wound in his arm but was still able to assist his pilot. Neither did it help that the  starboard engine had been damaged and was running out of control. At Dallachy they made a wheel up landing in the dark, quite remarkable in view of the damages to both men and machine. Both received the “Distinguished Flying Cross” for this considerable feat.

starboard engine had been damaged and was running out of control. At Dallachy they made a wheel up landing in the dark, quite remarkable in view of the damages to both men and machine. Both received the “Distinguished Flying Cross” for this considerable feat.

F/O Thompson from 455 Squadron, also made a belly up landing with his Beaufighter UB-Q at Dallachy. One other Beaufighter also made a belly landing. Many of those that did manage to land in the normal mode had shot up fuel tanks, missing parts of control surfaces and other damages. The ground crews were obviously in for a lengthy period of repairs.”

Photo (Web) Photo). One of the returning Beaufighters shortly after belly landing while another Beaufighter (in the background) is about to touchdown.

At 18:45 on the evening of February 9, 1945, the last Beaufighter landed at Dallachy. On reading other reports of the battle is was also learned that one Beaufighter had made a crash landing on the ice of Fjord Fjord and the Pilot survived. Following is a short narrative:

F/O JR Savard made a wheels-up landing on the ice with his aircraft on fire, likely after being hit by flak. The Beaufighter survived the crash, but turned upside down and trapped the crew. Norwegian civilians ran out to the aircraft but had to retreat when they were fired at by German soldiers. Savard and Middleton were seen to be pulled from their aircraft by flak crews, but Middleton was so severely wounded that he did not survive. Savard spent the rest of the war as a POW.

7. Allied Losses

14 aircrew (including 11 Canadians) killed in action and an additional 5 (including one Canadian, F/O JR Savard) taken as POWs. Photos of those killed is included in the Facebook Photo File (at the very bottom). Link to Photo Album

9 Beaufighters and one P-51 Mustang, destroyed.

22 Beaufighters, 11 P-51 Mustangs and 2 Warwicks along with their crews returned safely to base (three of the Beaufighters were badly damaged during the battle and had to make crash landings (all crew survived).

F/O Ramsdens Log Entry for February 9, 1945

German Losses

2 aircrew and 7 sailors. One of the air crew killed was a German fighter Ace, 28-year-old Leutnant Rudi Linz, who, at the time of the battle, held a record 70 kills mostly against the Russians.

5 Luftwaffe FW 190s were downed, 3 pilots baled out and were rescued.

7 Luftwaffe FW 190s returned safely to base

No serious damage was sustained by the Narvik Class destroyer, Z-33, or its escort vessels.

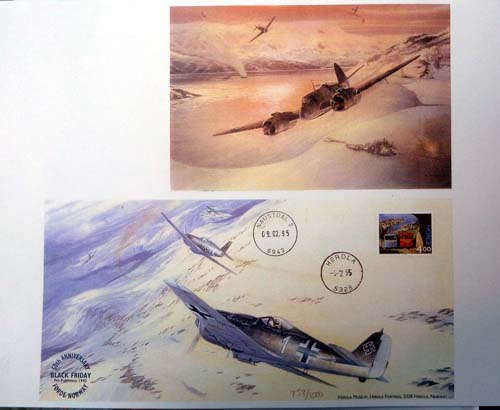

Black Friday Commemorative Postcard from Bert’s Files

Following that dreadful day, the only time he and his navigator ever talked about the danger, was before one of their last few missions into Norway. Roy had pulled Bert aside and ask Bert to be extra careful as he, Roy, wanted to get back safely to his bride.

Just a few days before, he had married English girl that he had met in southern England when he and Bert will still in bomber training. The marriage took place in Dallachy with Bert standing as Roy’s best man. At the time Bert’s thoughts were also about the young woman he had met in Regina before leaving for the war.

As it turned out the allies were slowly closing in on Germany and although the battles became fewer, the Germans always put up a still defence. By June the danger had slowly ebbed and after the Germans officially surrendered, Bert and his squadron had the great pleasure of acting as escorts in bringing a German submarine back to an allied base.

fewer, the Germans always put up a still defence. By June the danger had slowly ebbed and after the Germans officially surrendered, Bert and his squadron had the great pleasure of acting as escorts in bringing a German submarine back to an allied base.

Bert’s Files: Surrendering German submarine with the crew on the conning tower.

On another mission, they escorted a German destroyer. Unfortunately, it was not the Z-33, as that might have lent a little closure to that dreadful battle.

Within Norway, the battle at Forde Fjord came to symbolize the costs paid to free the country from Nazi occupation and those who fought the many battles were hailed as heroes by the people of Norway. Among other war memorials across Norway, one was built in the town of Naustdal at the foot of Forde Fjord. Several parts of downed aircraft and other memorabilia including F/O Ramsden’s Pilots Log book, are preserved in the museum.

8. End Note

While many who became experienced pilots during the war returned home to continue with a civilian or perhaps military flying career, F/O Ramsden decided to leave, mustering out on October 5, 1945 in Vancouver.

Before leaving the service, Bert travelled back to Regina where he and Marie married (photo left) on September 15, 1945. After mustering out on October 5, the young couple then returned to Nelson, Brtiish Columbia, where Bert joined his father’s business, becoming the Sales Manager. In Nelson, Bert’s older brother, Cecil Ramsden, was publisher of the Nelson Daily News.

Before leaving the service, Bert travelled back to Regina where he and Marie married (photo left) on September 15, 1945. After mustering out on October 5, the young couple then returned to Nelson, Brtiish Columbia, where Bert joined his father’s business, becoming the Sales Manager. In Nelson, Bert’s older brother, Cecil Ramsden, was publisher of the Nelson Daily News.

Over the years, Bert and Marie travelled extensively throughout the Western Provinces, something they both loved doing.

While the war experience has always remained fresh within Berts memories, he was lucky in that it did not overshaddow his life. Perhaps because of his being a pilot he was somewhat removed from the death and destruction that ground troops faced.

What he does reflect upon is how luck played such a big role in his having returned home safe and sound when so many of his good friends and flying comrades died in battle. Bert also appreciates the sacrifices made by hundreds of thousands of other young men and women around the world who gave their lives in the name of peace in order to preserve the freedoms we now often take for granted. Although death was not in the cards for Bert, he has no doubt that he would again place himself in harms way in order to preserve the world from tyrants such as Hitler.

We all need to periodically pause to give thanks to those brave men and woman who served during a very dangerous time in our history.

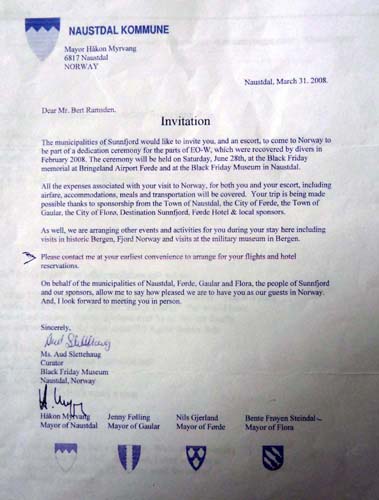

9. Black Friday Dedication Ceremony

Both P/O Bert Ramsden and P/O Miller Bryce, the last two survivors of Black Friday battle and of the 404 Squadron Flight Crew, were invited to travel to Norway for a on March 11, 2008, dedication ceremony for one of the downed Beaufighters that had recently been recovered from the icy waters of Forde Fjord. Following is a copy of the letter of invitation to Ramsden. The letter to P/O Bryce was likely very similar.

Harold McNeill

Footnote:

(I) A civilian on the ground some distance south and west of Forde, Johannes Gulbrandsen (born July 21, 1921), the father of Janegil Gulbrandsen, a member of the Victoria Torsken Klubben, witnessed the incoming bombers flying overhead and headed toward Forde Fjord. Mr. Gulbrandsen Senior, now 91 and living in Sola, Norway, often tells family and friends about the attack.

Note: Photo for this comment is missing and will be uploaded again by January 2014. March 22, 2013 The above photo of F/O Bert Ramsden (tying his shoe) and W/O Rumble (his navigator) was recently received from Terry Higgens, SkyGrid Studio/Aviaeology Publishing (Link)/CAHS journal (Link). Terry is currently researching, writing and illustrating a book on the history of the 404 Squadron of which F/O Ramsden and W/O Rumble were members. If you have any information or photos of the squadron activities or members, please contact Terry (skygrid@bellnet.ca) or myself (harold@mcneillifestories.com).

(12577)

Tags: 455 Squadron, 489 Squadron, Aunt Pat, Australian 455 Squadron, Beaufigher, Black Friday, CAHS Journal, Earl Davis, Edna Davis, F/O Bert Ramsden, F/S Earl Davis, Flight Sergeant Earl Davis, Forde Fjord, Lynn McNeill, Miller Bryce, Naustdal Norway, Nelson British Columbia, P/O Miller Bryce, P/O Pat Flynn, Pilot Officer, RAF Banff, RAF Dallachy, RCAF 404 Squadron, RCAF Regina, SkyGrid Studio, Squadron 404, Terry Higgens, TIger Moth, W/C Colin Milson, W/O Ray Rumble, Wing Commander Colin Milson, Z33

Trackback from your site.

Comments (2)

Dear Harold,

Thanks for taking the time to record this account of 404’s Black Friday.

I have been researching and documenting this squadron’s history for quite some time, working towards a book on it’s wartime operational history, and wonder if you might be interested in corresponding on the subject? I’m especially interested in getting in touch with surviving squadron members, or the families of departed members, in the interest of making the history as complete as possible.

Meanwhile, if interested you can find an excerpt from what I’ve written and illustrated thus far – albeit repurposed for Black History month in focusing the 404 Squadron life of Allen Bundy – by Googling “Vintage Wings Canada and Buffalo Soldier.” I’d send you the link, but see that this commenting system does not allow it.

With kind regards,

Terry at SkyGrid Studio / Aviaeology Publishing / CAHS Journal

This email from Pal Slavid in Norway received October 10

I simply must tell the following story; before a flight from Aberdeen to Bergen/Norway (it must have been around 2005), I had purchased a couple of “Pilot’s Notes” in a bookshop in Aberdeen. Among these one for the Mosquito. At the flight I was reading some pages in the biography of Douglas Bader (Reach for the Sky), and suddenly this elderly gentleman sitting beside me points to the book and says: “I knew this guy”. This gentleman turned out to be Mr. Bert Ramsden, and I was fortunate enough that he shared some of his story with me on this flight. And when I was able to pick up from my bag, a copy of the Pilot Notes which he had used during his training, we read it more or less together, and he commented with great knowledge. As an WWII aviator geek, this flight became a great memory for me, and I even got his signature on the Pilot Notes.

With great respect,

Pål